by Steve Chasin

I wrote this essay about my experiences with young people during their tours of the Virginia Holocaust Museum. They are often criticized and castigated because of their behavior. However, I found they responded in a refreshing manner that shows depth in their thoughts and beliefs. I hope the essay provides a different perspective from an outsider and encourages their parents.

Steve Chasin

Young people, those between seventh and twelfth grades, often get a bad rap. Yes, they can be noisy, disrespectful, rude, and self-important. However, this is not their essence. Beneath their bluster, behind their noise and laughter, are young adults who willingly wrestle with new and daunting questions.

Questions few adults today ever face, these young people eagerly tackle.

As a docent at the Virginia Holocaust Museum, I guide tours through the museum. My only experience with young people before becoming a docent was parenting my two kids decades ago. I approached my first tours with trepidation, wondering how a seventy-plus year old, New York-area born and raised Jewish man would connect and stimulate southern, (mostly) Christian-born and bred teenagers?

I wanted these students to feel and wrestle with the fears, hopes, and dilemmas of European Jews during the Holocaust. I hoped they would remember the lessons and be inspired to prevent future tragedies. But was I kidding myself? Aren’t these the kids that us oldsters paint as superficial and glued to their screens?

Touring the Virginia Holocaust Museum with Young People

On the tour, we begin with Hitler’s rise to power during the world-wide depression. Many of the students, if they know about the Depression in the United States, are surprised to hear it was a phenomenon around the world. I ask them to close their eyes and feel the shock when their parents tell them their family’s savings have disappeared, their father is unemployed, but the bills are still due. Some students’ eyes show surprise, others shiver, while a few nod from their own experiences.

To explain inflation, I mention that German families received baskets of their paper money, Reichsmarks, to spend each day with a warning that the basket of currency will buy less tomorrow. Some of the teens looked puzzled, and others chuckle at the thought of baskets of paper bills. They smile when I say that one dollar equaled one million Reichsmarks.

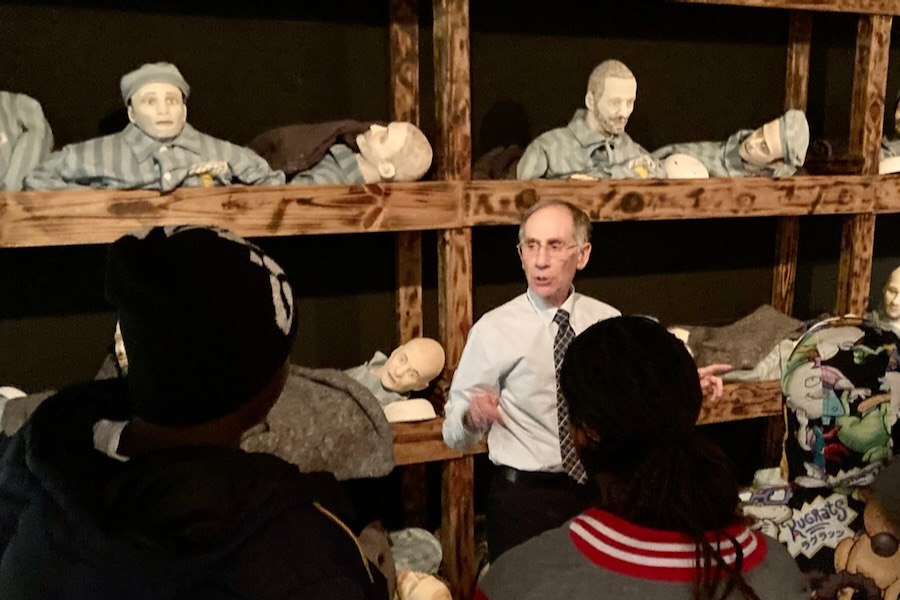

Next on the tour, we move to the recreation of the Dachau concentration camp. I ask them to identify signs of how Nazis dehumanized human people to control them. The students study the mannequins lying in the crowded three-tiered bunks and point out how the mannequins are bald and wear colored triangles on their pajamas. I explain how the triangle identified the inmate’s crime – such as being Jewish, gay, or exhibiting other traits that the Nazis determined to be anti-social.

I ask one student their first name, and then I share a number they may have been called if they had been forced into a concentration camp. The students shake their heads as they grasp the emotional importance of their name. Some even mention the history or reason for their first name, as though to protect themselves from this indignity.

As we stand at the ghetto exhibit (ghettos were enclosed and isolated districts where Jews were forced to live in inhumane conditions), I ask the students to imagine they are parents of young children who are starving or sick. What if they knew a child might be able to sneak out of the ghetto for food and medicine? Most quickly agree to send their child scavenging, until they learn the Nazis will shoot the youngster if caught. You can almost see their emotional tug-of-war between helping loved ones, versus losing the child. Most decide to keep their child safe within the ghetto’s walls. Their sense of life’s importance outweighed any other consideration.

I then appoint a student as the head of the ghetto’s council of elders. During the Holocaust, council members were charged with identifying friends and family to be deported from the ghetto and sent to their deaths. At first, they refuse, but this changes when I tell them their refusal means their families will be spared from the deportation – and the certain death that comes with it – for at least a short time.

A hush follows and some of the students tentatively point to others in the group while most are unable to choose. Finally, I ask the students in the group if they would find the elders on the council guilty of a crime at a post-war trial? One school group engaged in a lively debate with one side arguing for a guilty verdict to avenge a crime. The other side was equally vehement for acquittal because the elder on the council had no choice. Many others listened carefully, looked at each other and remained silent; grateful they don’t have to cast a vote.

As we walk through the museum, I hear the students’ discussions and comments. Some are arguing about their choices to select others to die, send their children outside the walls, or convict the council elder. Others quietly listen and wrestle with their experiences and teachings, trying to decide how they would respond to the circumstances. It’s heartening that few of the students run away from these horrible and challenging dilemmas.

Steve’s Message for Families About Their Children

This is horrible stuff. So why am I uplifted? There are clergy around the world exhorting young congregants to take responsibility to make the world a better place. For many young people, the Holocaust is their first exposure to humanity’s worst behavior. They often ask, How could this happen? Typically, the things these kids have learned in their homes and in churches argue against the Holocaust. They realize it’s easy to say you will help others, but what does this mean in the face of genocide? As I talk to them and see their faces, I believe they will draw upon their innate goodness and lessons to resolve their own and worldly dilemmas.

Finally, to the parents of these young adults I see at the Holocaust Museum on my tours, I say: Don’t worry. You’re doing a wonderful job of molding them to improve the world!

Read more about the Virginia Holocaust Museum in this article.