Several years ago, Martina, who was in her late sixties, felt she was experiencing too many memory lapses. She was concerned the gaps were caused by dementia, a cognitive condition she had witnessed in several close family members, so she asked her primary care physician if she was now on the same path.

“He said [some loss of memory] comes with age, and that I should write myself notes to help remember important details,” Martina says now. “I was worried because my three sisters had [dementia].”

That awareness led Martina to participate in a new VCU research study that explores a possible connection between physical function and cognitive decline. She heard about the opportunity through a wellness program at her senior apartment building in Richmond. “They figured I would be a good candidate, and I’m a person who, when someone asks me to do something, I’ll do it,” she says. “I’m pretty good at getting myself into stuff. I’m a cheerful person and like doing things.”

Adults who are sixty-five or older and interested in participating

in the VCU study can contact team members at 804-828-5930 or

email lcei@vcu.edu for more information.

The study, created by two Virginia Commonwealth University School of Nursing medical researchers, aims to identify physical precursors for dementia among adults ages sixty-five and older. Data collected from study participants could show when people are at a higher risk for developing dementia, which could lead to prevention or early treatment. That would be useful, as nearly ten percent of adults in the United States in that age group already have dementia – and the number is expected to rise sharply in coming years.

For this study, researchers are turning to technology as an easy way to collect data that shows a person’s digital biomarkers – heart rate, blood pressure, physical activity, and step counts.

“We want to develop a tool or means that can be used by lay people [to identify warning signs],” says Jane Chung, PhD, an associate professor in VCU’s Department of Family and Community Health Nursing. “Medical tests [for dementia] aren’t appropriate for frequent early detection because they’re invasive and expensive. If we can find some of the physical indicators based on digital biomarkers, they can tell us what’s going on with brain health.”

Another reason why Martina was willing to participate in the dementia research is because she has benefited from previous medical research. Martina has Crohn’s disease, which causes inflammation in the digestive tract. She credits past medical investigation for providing her with the information she needs to live well and avoid flare-ups. “I’ve been in remission for a good long time,” she says. “Red meat is bad for me, and I grew up on it. But I can’t digest it [now].”

Martina sees her participation in the VCU study on dementia as a way to expand the knowledge base for another challenging medical condition.

“People need to know about [dementia],” Martina says. “A lot of people don’t want to know, and they will deny [it] when family members have it. I think they’re just scared, and they don’t know what to do about it.”

Research Tools Can Help Unravel a Health Mystery

Lana Sargent, PhD, associate dean for Practice and Community Engagement at VCU’s School of Nursing, remembers having a casual conversation in the hallway with Chung when she first arrived at VCU roughly six years ago. “We started talking about our general interests and realized we both wanted to understand the relationship between physical function and cognitive decline,” Sargent says.

The two health services researchers decided to blend their expertise: Sargent’s efforts using cognitive evaluation in older adults who live in community settings and Chung’s use of sensor technology to assess mobility.

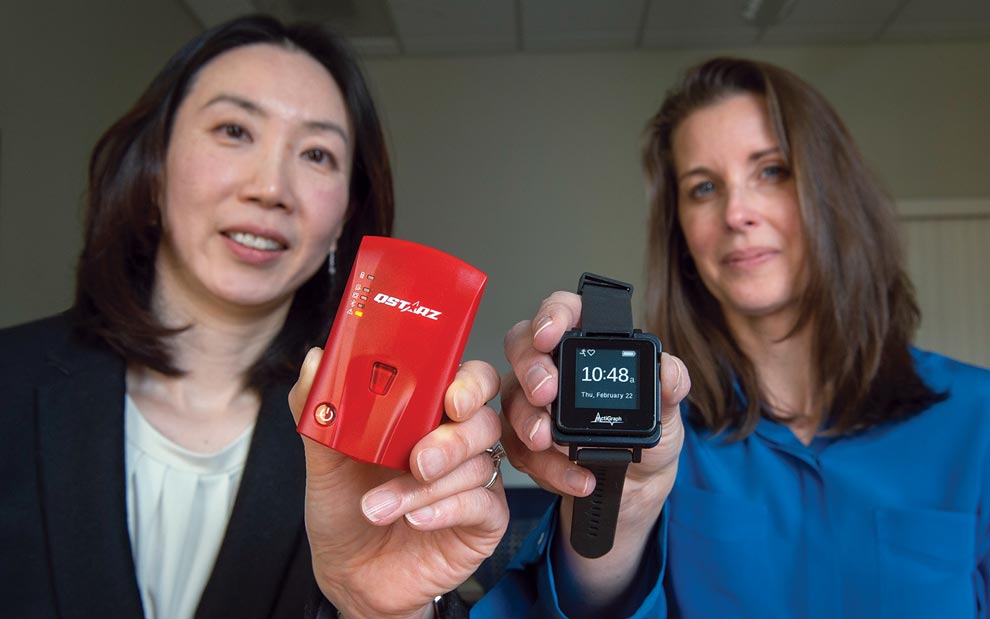

This dementia study, the pair’s most recent collaboration, netted a $3 million grant from the National Institutes of Health, enabling Sargent and Chung to fashion a five-year project that employs technology, questionnaires, and cognitive assessments. For seven days every six months, study participants will carry a portable GPS tracker – about the size of a car’s electronic key fob – and wear a wrist device that looks like a watch and functions as a fitness tracker. The two instruments will record participants’ data on mobility and physical activity, including how much distance a person covers, the duration of active time, and the intensity of the activity.

In addition to the quantitative (numerical) data, the researchers will collect qualitative, or non-numeric, data by asking participants to fill out questionnaires about social health factors, such as level of involvement in activities and their self-reported mental well-being. At the outset, participants also receive a cognitive assessment to determine if they are good candidates for the study, and they’ll continue to receive cognitive assessments over the course of their involvement.

By putting all that information together, Sargent and Chung hope to distinguish between typical cognitive issues associated with age – such as forgetting an acquaintance’s name or occasional difficulty finding the right word – and a serious developing problem.

“Dementia isn’t a normal part of aging, and it can be slowed and prevented,” Sargent says. “We can treat blood pressure [issues] with medications that can improve heart health, and we can do the same thing with your brain. It’s the non-normal changes that we want to screen for early.”

Early detection is critical, the researchers note, so interventions can happen as soon as possible. Just as cancer is an umbrella term that encompasses many different types of disease, dementia includes a range of neurological conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease, and frontotemporal, Lewy body, and vascular dementias (dementia caused by strokes). As medications and therapies continue to be developed for specific varieties of dementia, it’s important to try to obtain an accurate diagnosis as quickly as possible.

“We want to access treatment by catching [dementia] at the earliest stages so we can see which potential pathway [people] may be on,” Sargent says. “For example, cardiovascular history can lead to vascular dementia.”

Chung and Sargent are also particularly committed to recruiting study participants who come from historically underrepresented populations, such as low-income families, and racial and ethnic minorities. The researchers work closely with the VCU Mobile Health and Wellness Program, which provides services to communities with limited resources that may prevent people from receiving the medical care they need. “Many people don’t have cars or reliable transportation, so we go to where they live,” Chung says. “We talk with [potential participants] about research, technology, and brain health. We look for ways to get [people] engaged.”

Sargent says this type of research isn’t as clear-cut as investigations that have participants take part in a controlled study, but it yields important information as well as enables health care providers to connect with individuals in meaningful ways for the long term.

“Research can be much more organized in a clinic setting, but we’re going into people’s homes, living the chaos that they live,” Sargent adds. “We’re not just in and out of the community, doing research; we’re offering services. We do both health

and research together.”

One of the greatest challenges, the researchers agree, is the complex relationship that exists among all the factors that go into brain health. “When you have cognitive decline, you have changes in physical interaction,” Sargent notes. “And if you don’t have physical activity, that can lead to cognitive decline. This research is about helping us tease out that relationship.”

Prevention programs that address social isolation may be able to counter the effects of low mobility and early cognitive decline, Chung says. “We can look to community-based programs to reduce feelings of loneliness,” she adds. “It’s possible that a person who has low mobility and weak cognition [can do well] with a strong social network.”

Alzheimer’s and Dementia Resources in the Community

Madison Wilkins, director of development for the Alzheimer’s Association Greater Richmond Chapter, says the advancing age of the U.S. population is leading to greater attention for Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia.

“Think about this: The first discovery of Alzheimer’s was in 1906; 1970 to 1979 was the start of modern research; and the Alzheimer’s Association was founded in 1980,” Wilkins says. “There was such a stigma [surrounding the disease]. It wasn’t talked about, it wasn’t funded. But now, with our aging population, people are starting to see.”

A 2024 facts and figures report from the Alzheimer’s Association notes that the prevalence of all forms of dementia is rising along with the collective age of the U.S. population. By 2050, it’s estimated that there will be 82 million Americans age sixty-five or older, but many who have cognitive impairment may not realize it, either because their medical providers haven’t offered cognitive screenings or haven’t clearly shared the results of those tests.

“A number of potential harms may result from a missed or delayed dementia diagnosis,” the report notes. “These include delayed access to treatment, less time for care planning, higher costs of care, and negative impact on the individual’s physical or mental health or even the mental health of their family members and potential caregivers.”

Families need to realize that resources and support are available through the local Alzheimer’s Association, Wilkins says. “We have a 24-7 helpline at no cost,” she says. “Anyone can call us, at any time of the day, any day of the year. Our phone line is staffed with people who have master’s degrees in social work or higher. We also have support groups that people can attend in person or online. We go out and deliver programs to raise awareness, talk about what Alzheimer’s is and how [families] can make a plan, and also to encourage early diagnosis.”

The Alzheimer’s Association is also directly involved in the Pointer Study, part of the international Finger Study, which is a clinical trial investigating whether targeted lifestyle interventions can support brain health and prevent cognitive decline. “It’s a combination of physical activity, social activity, and management of heart-health risk factors,” Wilkins says. “What’s good for the heart is good for the brain.”

Fundraising is another important aspect of the Alzheimer’s Association, as the nonprofit relies on donations to provide for internal and external initiatives. Last year alone, the association allocated $100 million for research. In 2023 the Alzheimer’s Association GRVA Chapter reached over 5,000 families and individuals in the community through education, support groups, and early stage programs. They provided more than a thousand care consultations and had fifteen partnerships with community organizations focused on diversity, equity, and inclusion.

One fun way people can be involved, Wilkins says, is to participate in the association’s Longest Day initiative, a do-it-yourself fundraiser “where people can do whatever they want whenever they want,” Wilkins says. Activities can be small or large, and range from backyard mini-Olympics competitions to potluck meals where people pay to participate.

“We’ve had restaurants host concerts, where people dine to donate,” she says, adding the name for the effort is intentional. “Every day can feel like the longest day when you’re living with this disease or when you’re a caregiver [to someone with dementia],” she says. “So most of the Longest Day events that happen do occur in the month of June.”

Involvement and awareness of cognitive decline is important for everyone to understand, she says.

“Our name can be misleading,” Wilkins says. “We [provide] support for all forms of dementia, and our education and resources span [the spectrum]. We’re now stressing to caregivers that when a diagnosis of dementia comes, just like with cancer, they have to ask what kind of dementia.”

Making Connections: Community and Research

The VCU researchers are still recruiting participants in the greater Richmond area, ultimately hoping to enroll more than three hundred people who are willing to maintain their involvement for up to three years. Feedback from early enrollees is positive. “Many participants are excited about using the devices,” Chung says. “We intentionally chose [technology] that is very easy and doesn’t require a lot of work. We were wondering if they might be worried about seeing their results, but they are highly interested in seeing their data.”

That information is useful for everyone – research project participants, their medical caregivers, and their families. “The Baby Boomer generation wants control,” Sargent says. “If they knew there was something they could do, they would.”

Study participant Martina agrees that people should be willing to ask questions and face what comes. That’s a big part of why she’s participating in the VCU dementia study.

“If it happens, I don’t want to be angry; I just want to be able to accept it,” she says. “I think this research is important. The more research [doctors] do, the better they can come up with a cure. A cure might cost you [financially], but you’re going to be alive.”