It was spring 1894, early in President Grover Cleveland’s second term. A new company offering chocolate confections had recently been founded in Derry Township, Pennsylvania, in a town called Hershey. Avant-garde dancer and choreographer Martha Graham was born on May 11. And in Richmond, locals were enjoying a brand-new municipal building, which filled a full city block on Broad Street.

Less than a mile away from the new City Hall, a group of thirteen women met at the West Franklin Street home of Jane Crawford Looney Lewis to discuss the formation of a women’s club, an organization that would allow them and other like-minded women to gather for education and fellowship in a space that could be their own.

While the actual date of that meeting is lost to history, an invitation to join was mailed shortly after, with a deadline of June 11 to reply. By July, forty women had paid initiation fees of $5 each (the equivalent of $149.17 today) and annual dues of $10 (now $298.34). The purpose of the organization, according to the invitation, was to “cultivate Music, Dramatic Performances and Literature” and to occupy “a central location, in which will be found newspapers and magazines for the benefit of members.”

One hundred and twenty-five years later, The Woman’s Club of Richmond (TWC) continues to serve its mission to “educate, engage, and inspire today’s women with new ideas and people,” says Diane Beirne, the club’s executive director. Beirne says the club’s Monday afternoon meetings, held most weeks between the months of October and April, as well as an annual speaker series, lunchtime education program, special workshops and trips, all serve to support founder Lewis’ goal of encouraging “the delightful friction of well-trained minds.”

Reflecting the Time

Clubs for women became prevalent in the United States after the Civil War. In 1868, journalist Jane Cunningham Croly founded a women’s club called Sorosis in New York City, while anti-slavery advocate Julia Ward Howe founded the New England Woman’s Club in Boston. Both traveled throughout the nation, encouraging women to form clubs in their communities.

Women’s clubs ranged in style and purpose. In “Women’s Clubs: Women and Volunteer Power, 1868-1926 and Beyond,” published by the National Women’s History Museum, scholar Karen J. Blair, PhD, notes that some groups chose to “undertake serious study of intellectual topics and current events,” while others advocated for reform at local and national levels.

“Women’s clubs became the major vehicle by which American women could exercise their developing talents to shape the world beyond their homes,” Blair writes.

While membership tended to come from the white, Protestant middle class – women who were married to successful men and had household help – black women formed their own clubs. By 1890, there were enough women’s clubs in the nation for a General Federation of Women’s Clubs to be formed; in 1896, the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs was created.

From its earliest days, TWC in Richmond had education at the fore. In a history of the club, published in 1995, Sandra Gioia Treadway, PhD – a club member and now Librarian of Virginia – notes that Mary-Cooke Branch Munford was one of TWC’s founding members. A native Richmonder, Munford was keenly interested in education for herself as well as others. In her lifetime, Munford helped found (along with several other TWC members) the Richmond Education Association, was the first woman to sit on the Richmond school board, and served on the boards of visitors for both the College of William & Mary and the University of Virginia.

TWC’s first season in 1885 featured out-of-town speakers as well as local literary talents. Thomas Nelson Page, a popular Southern writer of the time, was one guest, as was Julia Strudwick Tutwiler, a women’s education advocate from Alabama. The club’s dedication to presenting its membership with speakers of note has continued throughout the years. In 1899, Woodrow Wilson – then a professor at Princeton University – spoke at the club, as did Chicago reformer Jane Addams. Later years would bring Amelia Earhart, Frank Lloyd Wright, Martha Graham, Robert Frost, actor Vincent Price, and two men who would later become presidents: John F. Kennedy and George H.W. Bush.

TWC’s first season in 1885 featured out-of-town speakers as well as local literary talents. Thomas Nelson Page, a popular Southern writer of the time, was one guest, as was Julia Strudwick Tutwiler, a women’s education advocate from Alabama. The club’s dedication to presenting its membership with speakers of note has continued throughout the years. In 1899, Woodrow Wilson – then a professor at Princeton University – spoke at the club, as did Chicago reformer Jane Addams. Later years would bring Amelia Earhart, Frank Lloyd Wright, Martha Graham, Robert Frost, actor Vincent Price, and two men who would later become presidents: John F. Kennedy and George H.W. Bush.

The fall 2017 presentation from Hillbilly Elegy author J.D. Vance, was so popular that it had to be relocated from the club’s headquarters, the Bolling Haxall House on West Franklin Street, to St. Paul’s Memorial Church, to accommodate the crowd.

“The board made the decision not to limit guests our members could bring,” Beirne says. “Some members brought their whole book clubs!” The 2019-20 season of speakers includes Pulitzer-Prize winning author Anna Quindlen and USA Today Washington bureau chief Susan Page.

Current board president Margaret Lundvall, a member since 2012, says she joined TWC for the programs and the fellowship. “We are extremely fortunate to have a broad range of speakers and topics,” she says, noting that the forthcoming year will include presentations on race relations, vaccines, and upcoming elections. “Anyone who attends a Monday afternoon program or any of our special events can be

sure they will find something interesting and elevating,” Lundvall adds. “I have made friends here with common interests, and friends who have made my life more interesting.”

Noting that the members of TWC have a history of community involvement and activism, Lundvall says it’s essential that programs encourage members to be active today. “They deepen our knowledge and appreciation about issues facing our community, and challenge and enlighten us with information about relevant issues and subjects,” she says. “As I see it, our offerings are the catalysts that energize us all to seek and pursue our passions.”

Passion for Education

From its beginning, TWC members have turned their education into action. In 1901, after hearing about the struggles of the Nurses’ Settlement, a nursing program at Old Dominion Hospital, several members were inspired to establish and fund the Instructive Visiting Nurse Association (IVNA), which provides home health care and patient advocacy for those in need and is still functioning.

In 1904, members of TWC heard about the lack of libraries in rural areas of the state. In response, members donated books to create traveling libraries and within a year, three had been formed.

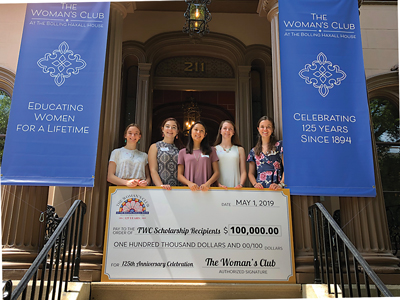

In 1911, at the urging of charter member Jane Meade Rutherfoord, TWC awarded an educational scholarship to be given annually to a “Virginia mountain girl.” In 1921, the club endowed a scholarship for young women who wished to attend college. Since then, more than 500 young women have received financial support from TWC for higher education. In recent years, each scholarship was $8,000 for five women ($2,000 given annually to each student). But this year’s awards were $5,000 per year for four years ($20,000 for each recipient).

“The increase is a result of an outpouring of support for this initiative among TWC members to meaningfully highlight this anniversary and our mission to empower women,” Beirne says.

The recipients are known as Mary Munford Scholars in recognition of charter member Munford, who also has a Richmond elementary school named for her.

Shared Experiences

Frances Whitlock Kay, who has been a member since 1980, acknowledges that when she first joined, she did so because she was looking for a “deviation from carpools and parental volunteerism,” and TWC seemed like a different kind of women’s club, one with a diverse array of speakers covering topics “many would probably not explore otherwise.”

In 2003, Kay was asked to join the board of the Bolling Haxall House Foundation, the entity that owns and maintains TWC’s headquarters. It was then, she says, that she became fully aware of the commitment TWC has to the Richmond community.

“I’m proud of [the foundation’s] role in restoring and maintaining the historic house when many organizations were electing to move from downtown,” she says. “TWC is so much more than an organization for socialization – it is a valuable multipurpose community resource!”

Members are always welcome to bring guests to TWC programs, Beirne notes, adding that the Bolling Haxall House may be rented by nonprofit organizations at reduced or no cost for their own events. For example, the Concert Ballet of Virginia has held performances in the auditorium of the house since the mid-1980s. In June, the Asian American Society of Central Virginia hosted a reception at the house for the new Indonesian ambassador to the United States.

Dr. Betty Neal Crutcher, who joined in 2017, says her membership has been especially valuable to her as a relative newcomer to Richmond, having moved here in 2015 when her husband, Dr. Ronald A. Crutcher, became president of the University of Richmond.

“In the many cities that…I have lived, it has been especially gratifying to step aside from the busyness of everyday living to gather for a time of listening and sharing, and to learn from distinguished speakers who share new perspectives,” Crutcher says. “In a short period of time, TWC allows the newcomer like myself to network with a lot of different women and see what we have in common. The club allows us to be ambassadors for one another and gives us an opportunity to learn about new things.”

TWC president Lundvall says the founders had a clear vision: “[They] recognized the interest in education, addressing provoking topics, and the energy of women learning together,” she says. “In a time when education of women wasn’t a given, they founded a club which provided information and enlightenment to those who sought it.”

And TWC is still relevant, Lundvall says. “Regardless of the implied state of equality in today’s community, I feel there’s still a need for a venue where women can gather to share ideas and opinions in a safe and non-judgmental environment.”

With a recent strategic plan in hand, the club is taking steps to ensure its relevance for current as well as future members. Regular Monday afternoon meetings will continue, but additional programming to accommodate different member schedules will also be offered. Special events – a cycling excursion along the Virginia Capital Trail, a Liquid Lunch tour of Scott’s Addition, and a weeklong trip to Newport, Rhode Island – have been suggested by members as well.

“Women are so busy today – there are so many pulls on our time and energy,” Beirne says. “The Woman’s Club offers a place where women can do something just for themselves.”

Past and Present

Even as member activities expand and change, TWC maintains its relationships with long-standing partners. The Concert Ballet of Virginia began using the Bolling Haxall House auditorium for performances in the 1980s and continues to hold gala events at the club. The Junior Assembly Cotillion, which offers dance classes to middle schoolers and high schoolers, began meeting at TWC in 1950 while under the ownership of TWC member Cleiland Donnan and continues to do so with its current owners.

While the question of women’s suffrage was divisive in the club’s early days, it’s clear that members were active in social – some might even say political – causes, even without the right to vote.

Voices from the Garden: The Virginia Women’s Monument, which is slated to be dedicated this month on Capitol Square, features a glass Wall of Honor, inscribed with the names of two hundred and thirty notable women of Virginia. Of those, sixteen are past members of TWC, including notables Lila Meade Valentine (1865-1921), president of the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia; Nancy Astor (1879-1964), first woman elected to Britain’s Parliament; Laura C. Martin Wheelwright (1871-1948), founder of The Garden Club of Virginia’s Historic Garden Week; and Mary Tyler Freeman Cheek McClenahan (1917-2005), activist and philanthropist who worked to improve race relations and provide affordable housing through her founding efforts with the Richmond Urban Forum, Richmond Renaissance, and the Richmond Better Housing Coalition.

The club’s membership has generally remained steady throughout the years, often with prospective member waiting lists. With steady demand from after World War II and through the 1950s, TWC enlarged its membership to 1,400, the current limit.

“For one hundred and twenty-five years, The Woman’s Club has been a place where we witness fellowship, intellectual curiosity, and every kind of generosity – of time, of labor, of spirit,” Beirne says. “The members have not only built a powerful community for themselves within the always bustling hub of Bolling Haxall House, but they’ve taken those passionate energies into the communities around them … ultimately becoming an integral and depended-upon partner and friend.”

Special thanks to Sandra Gioia Treadway, PhD, author of The Woman’s Club, Women of Mark: A History of The Woman’s Club of Richmond, Virginia, 1894-1994, an invaluable resource in the researching of this article.

Photo: Mellissa Brugh (Diane Beirne)

All About the Bolling Haxall House

After renting space in different downtown buildings in its early years, The Woman’s Club was able to purchase a building, thanks to steadily increasing membership and rents. In 1900, with Mary-Cooke Branch Munford as president, the club purchased a house at 211 East Franklin Street that had been built in 1857 for businessman Bolling Walker Haxall and his wife, Anne Triplett Haxall.

The Italianate-style home of three floors was finished with brown stucco and had an entry porch with a second-floor balcony and balustrade, and a roof-top cupola. In the beginning, rooms were rented to other organizations, providing a revenue stream to help offset the purchase cost.

Over the years, TWC maintained the house as any other property, with needed repairs and the addition of an auditorium in 1916. In the 1960s, an extensive renovation was undertaken, and the house was placed on the Virginia Landmarks Register and on the National Register of Historic Places in 1971.

In 1984, TWC initiated a capital campaign to fund restoration of the house to its original appearance, complete with historically appropriate furnishings and accessories. In 1990, the Bolling Haxall House Foundation was established to provide separate governance and oversight for the house.

The Bolling Haxall House is a popular location for weddings and corporate and community events. The house was featured in a PBS special, Reconstruction: America After the Civil War, and was also used as a location for a 2018 episode of ABC’s The Bachelorette.

Renowned Author Anna Quindlen Visits The Woman’s Club

“Women weave the world, thread by thread, every day. They are the hammock in which I rest.”

Pulitzer prize-winning and bestselling author Anna Quindlen kicks off The Woman’s Club 2019-20 Monday speaker series on October 7, with a talk titled “Women in the 21st Century: The Balancing Act.”

Quindlen, who began her writing career as a newspaper reporter, is well-known for her personal columns and her many books, both fiction and nonfiction, which have sold millions of copies. She won the Pulitzer Prize for commentary in 1992 while she was a columnist at the New York Times.

Quindlen, who began her writing career as a newspaper reporter, is well-known for her personal columns and her many books, both fiction and nonfiction, which have sold millions of copies. She won the Pulitzer Prize for commentary in 1992 while she was a columnist at the New York Times.

Her second novel, One True Thing (1994), served as the basis for the 1998 film starring Meryl Streep and Renée Zellweger about a young career woman who steps in as a caregiver for her dying mother. Nanaville, Quindlen’s most recent book, is a celebration of being a grandparent. It was published in April 2019.

How would your writing path be different if you were starting today?

Well, I would hope in one respect it would be exactly the same. I would still like to begin as a general assignment newspaper reporter, because it’s the best job around. But instead of calling in to the recording room on deadline, I suppose I’d be typing my story on the screen of my phone with my thumbs. And what was once a single evening deadline for the paper, maybe a second if the story was breaking, would become a 24/7 for the digital edition. But that’s just the peripherals. I would still be doing street reporting, probably with an old reporter’s notebook. I like those notebooks.

Did you expect to write fiction as well as nonfiction when you began your career?

Actually, I’ve always wanted to be a novelist. I’ve always been a constant reader, mesmerized by books, and I remember as a kid just looking around the library at Dickens and the Brontes and Agatha Christie and Harper Lee and thinking, Yes, just like them, please. When I was eleven, I tried to figure out where my books would be shelved. Between Proust and Ayn Rand. I went into the newspaper business because I couldn’t figure out how to pay the rent with fiction. Then I loved it so much that I just stayed for a long time.

Thanks to the Internet, more people than ever are sharing personal stories and thoughts. How has this changed what published writers have to offer?

I guess I should say it’s changed a lot, but at least for me it hasn’t. I don’t have a real presence on social media. I don’t want to be any more out there than I already am. I think lots of readers, and writers, honor the old familiar ways. I remember when a commencement speech I was supposed to give – and didn’t because of anti-abortion protests – started to make the rounds online because I’d sent it to someone. You could find it on your computer, no problem. But when we decided to do it as a little book called A Short Guide to a Happy Life, it sold and sold and sold. It’s been almost twenty years, and it’s sold about a million and a half copies. Yet, you can still read it online. In a digital age, it made me understand how much people still value actual books.

Over the course of your career, you have written about women’s lives at every age and stage. Do you see a common theme in womanhood, no matter what the age?

Wow. I just read that question and started to tear up. Who woulda thunk? It’s because my female friends are the bedrock of my life. So, themes: Generosity. Connection. Community. Women weave the world, thread by thread, every day. They are the hammock in which I rest.

Your latest nonfiction book is about being a grandparent. What’s a lesson you took from your own grandparents that you hope to share with your grandson (and other grandchildren)?

I think I learned from my grandparents that I was part of something bigger, deeper, more important than myself, and that I should never forget where I came from or that I had an obligation to pay it forward. There was always the sense that understanding the world, and being empathetic and honest, was a function of seeing yourself not only as an individual but as a link in a great chain of people. You can’t afford to be the weak link in that chain.

I’m the granddaughter of immigrants on my mother’s side, and my grandchildren are half-Chinese. So I stand as a testament, and they will, too, to the fact that the strength of America lies in its willingness to welcome its citizens from elsewhere. Any opposition to that notion is opposition to my Italian grandmom and grandpop, and to Arthur and Ivy Krovatin (my grandchildren). And I’m just not having any of that – at all.