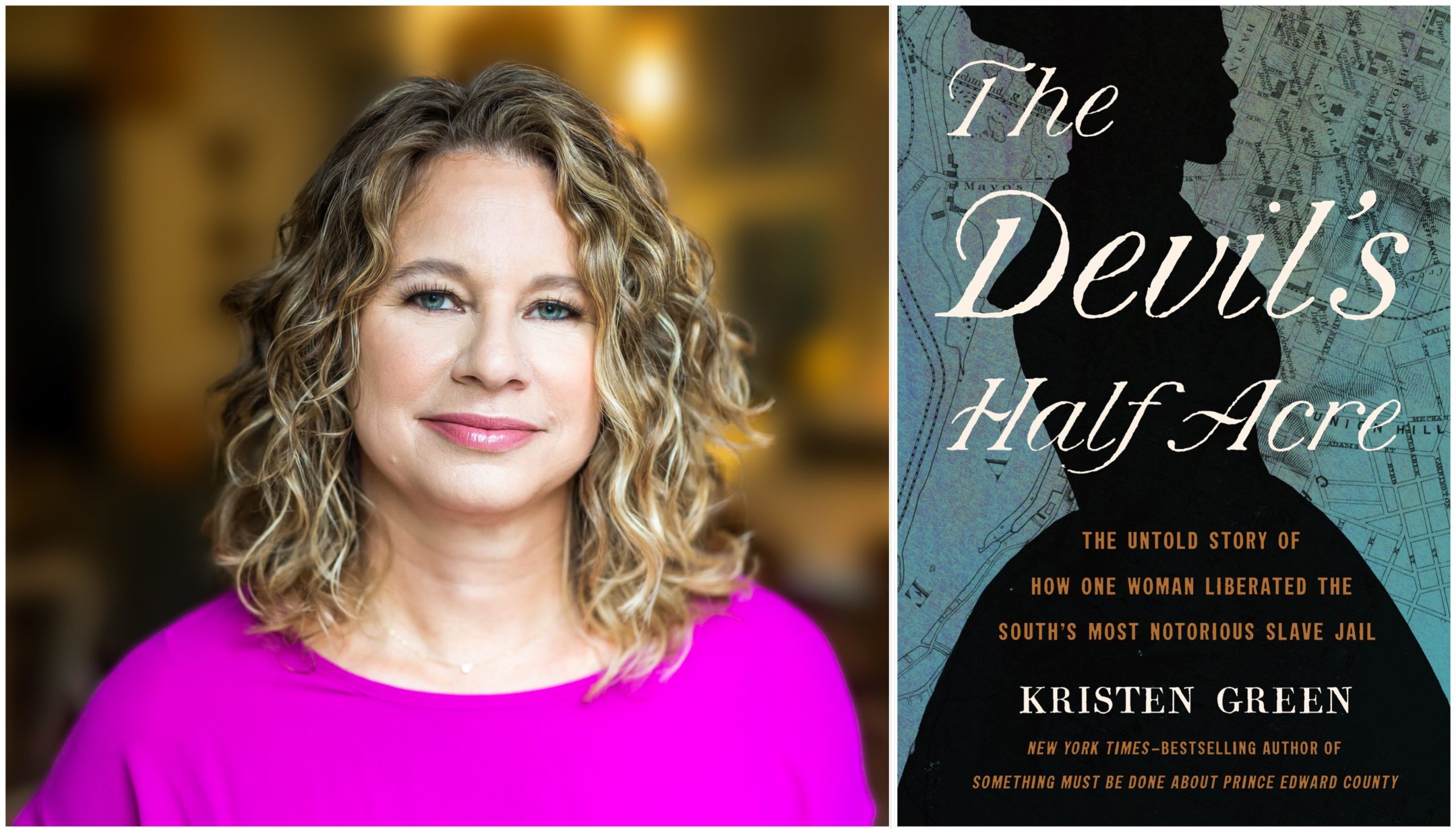

Kristen Green had never heard about the slave jail Devil’s Half Acre in Shockoe Bottom until she was on an assignment for the Richmond Times-Dispatch. What she subsequently learned about the slave trade in the area compelled her to write book number two, The Devil’s Half Acre: The Untold Story of How One Woman Liberated the South’s Most Notorious Slave Jail. The book was released this April.

“I was doing some background research when I came across an article in the Smithsonian Magazine outlining an archeological dig at Lumpkin’s Jail. What struck me was a few lines about an enslaved woman named Mary Lumpkin. It said she acted as slave trader Robert Lumpkin’s wife. I wanted to know more about that,” says Green, a New York Times bestselling author.

Research shows that at the age of thirteen, Mary Lumpkin was forced to bear the children of Robert Lumpkin. When he died, Mary inherited the jail and transformed it into God’s Half Acre, a school where Black men could have access to education. The school later became part of Virginia Union University, one of Virginia’s five HBCUs.

Green, who moved to Richmond in 2010 and lives in the Fan with her family, was in the middle of another book project when she discovered this information so she didn’t act on it immediately. She returned to the story of young Mary Lumpkin in 2014 after her first nonfiction book, Something Must Be Done About Prince Edward County, was finished in 2014.

“The Devil’s Half Acre took me seven years from start to finish,” she says. “My knowledge of slavery was so shallow, I had to ground myself in the history before I could tackle the project.”

For Green, the writing process began early in the morning. “I work when my brain is the sharpest and I have the least distractions,” says Green, the parent of two daughters — Amaya, fourteen, and Selma, thirteen. “I write in chunks so I would write smaller bitesize pieces. I jump around a lot.”

What she learned about Mary Lumpkin fascinated her. “I thought it was incredible that she was able to purchase a home in her name in Philadelphia before the Civil War while she was still enslaved in Virginia. She was in Philadelphia by 1860,” she says. “Also, she had five kids, two daughters and three sons, that survived adulthood. They were all children of Robert Lumpkin.”

Green was able to build a family tree for Mary and follow the descendants of the enslaved woman‘s first born child to Oregon and California.

“Carolivia Herron, a Howard University professor, historian, and Black resident of Washington D.C., had long known the story of her ancestor [Mary Lumpkin], and she provided valuable insight,” says Green, who did much of her research through census reports. “I found Mary’s life so interesting.”

The Inspiration Behind the Writing

The idea for Green’s first book, Something Must Be Done About Prince Edward County, was also serendipitous. A longtime reporter, Green was inspired after reading a story about 16-year-old Barbara Johns, who led a student walkout from her Prince Edward County high school because of the conditions at her all-Black school. After the Brown v. Board of Education decision, Prince Edward County closed its public schools to protest integration. They remained closed for five years during the racist policy of Massive Resistance instituted by Senator Harry F. Byrd Sr.

“I grew up knowing the schools had closed. I didn’t know why. A white academy had been founded and my parents went there,” says Green, who grew up in Farmville and also attended Prince Edward Academy, which did not admit black students until 1986.

Reading the stories of the impact that action had on Black families – about 1,700 Black children were denied an education – was profound, she says. “I knew I had discovered an important story … that wasn’t that long ago. It [closing public schools] affected so many children, and it had profound implications on what that community is like today. I loved the idea of bringing it to the present.”

Because Green attended the segregated academy she had a unique perspective on the subject. “I was there in 1986 when they admitted the first Black student,” she says.

Writing and Parenting

Green’s daughters, Amaya and Selma, were young when their mother was writing her first book.

During the writing process, Green worked when her daughters were at school, but after the book was published, “we did travel around for my book events,” she says. “Books take over your life, but it’s something the kids can be proud of.”

While she doesn’t know if her daughters will write books, they may, she says. “They have a good role model for how to do it. Selma used to squeeze in next to me on the couch in the early mornings while I edited the Devil’s Half Acre. She learned firsthand how it is done.”

Both daughters have their own creative outlets. Both are dancers and musicians.

“They are already writing songs,” Green says. “They have a band called Buenas that performs in Richmond.”

Now, it’s Green’s turn to be proud.

Green’s books are available at local booksellers and online here.