How Aka Pygmies Are the Best Fathers in the World

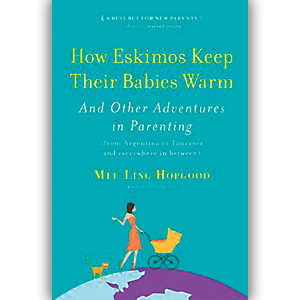

Despite growing globalization, parenting techniques around the world continue to vary widely. In How Eskimos Keep Their Babies Warm by Mei-Ling Hopgood, she blends research, interviews, and personal experiences to prove there are many ways to be a good parent. In my first blog on this book, I looked at the following chapters: “How Kenyans Live Without Strollers” and “How the Chinese Potty Train Early.” While most of the title is directed towards moms, the chapter, “How Aka Pygmies Are the Best Fathers in the World,” ended up captivating me the most.

Despite growing globalization, parenting techniques around the world continue to vary widely. In How Eskimos Keep Their Babies Warm by Mei-Ling Hopgood, she blends research, interviews, and personal experiences to prove there are many ways to be a good parent. In my first blog on this book, I looked at the following chapters: “How Kenyans Live Without Strollers” and “How the Chinese Potty Train Early.” While most of the title is directed towards moms, the chapter, “How Aka Pygmies Are the Best Fathers in the World,” ended up captivating me the most.

According to Hopgood, the Aka are a community of approximately 30,000 people living in the forest that border the Congo and the Central African Republic. Hopgood explains, “They are among the last true hunter-gathering people on earth.” Hopgood references the work of anthropologist Barry Hewlett, author of Intimate Fathers: The Nature and context of Aka Pygmy Paternal Infant Care, when she relates how Aka children spend equal time with both parents. Apparently, “Aka dads harness their babies in infant slings and take them on hunts, babysit when moms need to set up camp, and bring them along when they let off steam with the guys at a palm-wine happy hour,” Hopgood explains.

Hopgood reports how Barry Hewlett claims, “There’s a level of flexibility that’s virtually unknown in our society.” And as far as Hopgood is concerned, “The Aka have become living proof that fathers can and do participate evenly in child care, if called upon, if expected, and if given the right circumstances and support.” So why aren’t more fathers like this? Hopgood explains that according to anthropologist Margaret Mead, “Tribes and nations that expect their men to go to war tend not to let their men get too close to their young.” The Aka are an example, Hopgood points out of a non-warring tribe. Hopgood also explains how “expectations feed the way we behave. If we assume that men shouldn’t be affectionate with children, they won’t be.”

While more and more research is showing how children benefit from time spent with their fathers – more sociable, adaptable, and better performing in school – Hopgood reports, according to the Fatherhood Institute, of the 156 cultures studied only 5% helped fathers be closer with their little kids. A perfect example of this is paternal leave. Hopgood relays, “The United States is one of the stingiest of the world’s wealthy countries when it comes to any kind of paternity leave…placing last with zero weeks of paid leave required by law and twelve weeks of upaid leave only for employees of firms with more than fifty employees. By contrast, Sweden offers dads two months paid leave, according to Hopgood. She writes, “If daddy didn’t take it, the family would lose it.” As you might imagine, 85% of Swedish fathers take paternity leave.

When my first daughter was born, I was teaching in New Jersey and able to secure my pension if I finished out the school year, so my husband, a Federal employee, took paternity leave. He still considers those months as some of the best in his life (and will frequently tease that all her achievements stem back to their time together ;-). While our declaration that my husband was on paternity certainly turned a few heads, it’s something I wish every dad and child could experience.

As far as Barry Hewlett is concerned, “Our value of children has to increase.” Hopgood admitted that her and her husband negotiated daily over who would take care of their daughter. Ultimately, she came to wonder if they shouldn’t be arguing over how they could spend more time with her. This idea really resonated with me, especially with summer approaching and so many families making arrangements to busy their children so they can get their work done. What if American parents abandoned their quality versus quantity mindset and took a lesson from the Akas? Anthropologist Barry Hewlett argues, “The Aka relationship is special not because of how a father interacts or plays with his child but because father and child know each other exceptionally well because of the time they share together.”

So if you’re up for experimenting with your tried-and-true traditions, check out Mei-Ling Hopgood’s How Eskimos Keep Their Babies War. Her chapters on “How Polynesians Play without Parents” and “How Mayan Villagers Put Their Kids to Work” are really interesting as well. You might not be ready to adopt all of their practices, but at the very least, you’ll have a world of new ideas.

Follow @WinterhalterV on Twitter for updates on blog posts or like Parenting by the Book on Facebook.