Richmond, Virginia is home to one of the preeminent art museums in the nation. Explore all VMFA has to offer its visitors.

As I walked through the galleries of the Denver Art Museum last November, taking in the exhibition Whistler to Cassatt: American Painters in France, two thoughts crossed my mind: what a wonderful exhibition for families, and how lucky Richmond is to have the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

Whistler to Cassatt, opening at VMFA in mid-April, includes 113 artworks made between 1855 and 1913 and focuses on the lessons learned by American artists who went to France to hone their craft. According to Dr. Susan Rawles, associate curator of American Decorative Arts at VMFA, the exhibition showcases a critical moment in art history. “The pursuit of classical art of nature and royal subjects is being challenged [during this time] by a realist trend in which the world is presented as the artist perceives it,” she says. “Art doesn’t have to be in a particular style. There’s a looser brush, earthier tones; the point is to present life as it is.”

Whistler to Cassatt, opening at VMFA in mid-April, includes 113 artworks made between 1855 and 1913 and focuses on the lessons learned by American artists who went to France to hone their craft. According to Dr. Susan Rawles, associate curator of American Decorative Arts at VMFA, the exhibition showcases a critical moment in art history. “The pursuit of classical art of nature and royal subjects is being challenged [during this time] by a realist trend in which the world is presented as the artist perceives it,” she says. “Art doesn’t have to be in a particular style. There’s a looser brush, earthier tones; the point is to present life as it is.”

And that’s what viewers see in the artworks included: life as it is. A girl walking on a beach dune, holding her hat so the wind doesn’t take it. A boy learning how to carve a wooden shoe under the watchful eye of a craftsman. A young woman stroking the dog sitting peacefully in her lap. As a parent who once took her children to museums to educate and enlighten them – and to provide an activity on too-hot or too-cold days – I found myself thinking about the conversations I could have with my children if they weren’t past the age of needing me to talk to them about art. (They educate me now.) But the opportunity for you and your family to explore Whistler to Cassatt, and talk about what you find, shouldn’t be missed.

Discovering Art History

VCU Assistant Professor of Art Education Lillian Lewis, PhD, remembers many visits to the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, as a child. There were family excursions and class trips with her father, a history professor, when he would bring students from his Western Civilization classes to the museum. The time at the Kimbell made a big impression on her.

“I developed a genuine friendship” with a painting by the Dutch artist Piet Mondrian, Lewis says. “Year after year, I could visit that painting and find something new.

“Art appreciation gives us a richness and complexity of experience that we can bring to our interactions with other people, our environment, and the work we do,” she adds.

Lewis, whose primary focus is teaching students who hope to become art teachers themselves, notes that art museums are excellent venues for families to explore together. “There are so many points of entry,” she says. “There is no single right way to look at or experience or connect with works of art or connect works of art with each other. So many of the discussions in art museums don’t have to rely on a distinct narrative. We can talk about art descriptively, comparatively, and relationally. I see art museums as a place for vivid entanglements.”

Lewis acknowledges art museums might feel different from more hands-on museums, like children’s museums or science museums. “Exhibitions [at child-centered museums] support interaction and approach learning from a much more conversational or bite-sized approach, but there’s no reason to think that art museums can’t be bite-sized,” she says. “We have a tendency to think of an art museum as a place you go once a year with your whole family, and you should try to see all the artwork. Art museums are not theme parks; you don’t have to see every artwork.”

Instead of approaching an art museum like you would a buffet, where endless sampling is available, Lewis suggests a different approach. “Nobody leaves a buffet feeling comfortable,” she says. “I would strongly encourage families to think of an art museum as a tapas restaurant, with small plates. Go and enjoy one thing deliciously.”

When should parents introduce their children to an art museum? “As soon as you can get a baby into an art museum, do it,” Lewis says. VMFA classes can help parents discover ways to talk with little ones about art, focusing on color, faces, even animals. “Notice what [the baby is] noticing, and let them lead the experience,” Lewis advises. “As they become more verbal, they can build vocabulary and build connections. Parents can practice careful looking and describing [with their baby], and help them discover their

When should parents introduce their children to an art museum? “As soon as you can get a baby into an art museum, do it,” Lewis says. VMFA classes can help parents discover ways to talk with little ones about art, focusing on color, faces, even animals. “Notice what [the baby is] noticing, and let them lead the experience,” Lewis advises. “As they become more verbal, they can build vocabulary and build connections. Parents can practice careful looking and describing [with their baby], and help them discover their

own preferences.”

As the child becomes older, conversations expand. “Art museums allow us to make connections, [and] any two things can be connected or reconnected or thought of in different configurations. That can be led by children.”

The process of seeing and making connections among different artworks goes beyond simply liking what you see on display, she adds. “Understanding relationships from a personal standpoint is so important,” she says. “Those are translatable ways of thinking that are really valuable in both the philosophical realm and the practical realm.”

Those conversations also foster critical thinking skills, she adds, as discussions can explore similarities between artworks that might be noticed by one family member but not another. “Art museums allow us to make connections, [and] any two things can be connected or reconnected or thought of in different configurations. That can be led by children,” she notes. “There are so many times when we need to see things obliquely and make complex connections in our everyday lives. Art museums provide a space where we can cultivate those ways of thinking.”

When it comes to keeping kids engaged in a museum, parents can employ multiple approaches. Lewis says a purpose-driven visit is useful because it creates a clear goal and sets limits, so the experience isn’t overwhelming. Parents can use the framework of a treasure or scavenger hunt, where members of the family try to find representations of trees or animals. A thematic approach might ask which works depict a particular season. Or it can be as simple as asking children to find three works of art that make them smile.

“In the same way we want them to be helpful at home, we can break down a visit into smaller tasks,” Lewis says. “You don’t want to enter aimlessly with the goal of seeing as much as you can.”

Remember, too, that museums routinely change what is on view. Special exhibitions, like Whistler to Cassatt, and rotating items from the institution’s permanent collection bring fresh opportunities to every visit, Lewis says. “You can go to VMFA every single day for the rest of your life, and you’ll never step in the same stream twice,” she says.

A Unique Moment In History

Rawles, the VMFA curator, says there are abundant conversational opportunities with Whistler to Cassatt, thanks not only to the breadth and variety of the artworks included but the time period represented, which was transformational for both the United States and art. In the U.S., the period between the Civil War and World War I saw the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, the rise of the Gilded Age, an influx of immigrants, and the ascendancy of New York City, which combined its boroughs in 1898 to compete with Chicago, which had been the dominant metropolis in the country.

In the art world in Europe, artists were breaking with tradition that emphasized classical and highly polished art forms. “There was a new view of human agency and how society creates human conditions,” Rawles says.

An outward sign of the tension in the art world was the Salon des Refusés, which was created in 1863 by Napoleon III to showcase hundreds of artworks that had been rejected by the traditionally focused jury of the French Academy of Fine Arts (Académie des Beaux-Arts) for the annual Salon, a massive art show. The creation of a show in opposition to the Salon acknowledged that while artists might still seek training at the Academy’s School of Fine Arts (École des Beaux-Arts), they were also exploring new techniques in the outdoors and in smaller, private studios.

This meant American painters who had gone to Paris were finding their own paths. “[At this time] Americans are selectively picking and choosing what they do,” Rawles says. “They’re not completely giving up academic form and not completely doing Impressionism. They’re creating a hybrid approach.”

When the French-trained Americans returned home to the U.S., Rawles says, their hybridized approach shifted further, to appeal to a different audience. “They had to combat the sense that their work is ‘Frenchified’ and no longer American,” Rawles says. “They had to modify their work to suit tastes.”

American artists whose work is featured in the exhibition include James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Mary Cassatt, John Singer Sargent, Winslow Homer, and Edward Hopper, as well as Henry Ossawa Tanner, a Black American artist, and Walter Gay, Henry Mosier, and Frank Myers Boggs, the first three American artists whose works were purchased by the government of France after being shown at the Salon.

The artworks in the exhibition will be accompanied by educational material, so viewers can think about their placement in history as well as what they depict. An education area included within the exhibition will feature recognizable icons of the time – Abraham Lincoln, the Statue of Liberty (a gift from France, dedicated in 1886), the bald eagle – that, Rawles hopes, will spark conversation.

“When families get to the education space, that will be a moment to talk about what’s happening in the U.S. at the time,” she says, adding, “Art is resonant of the time period when it was made.”

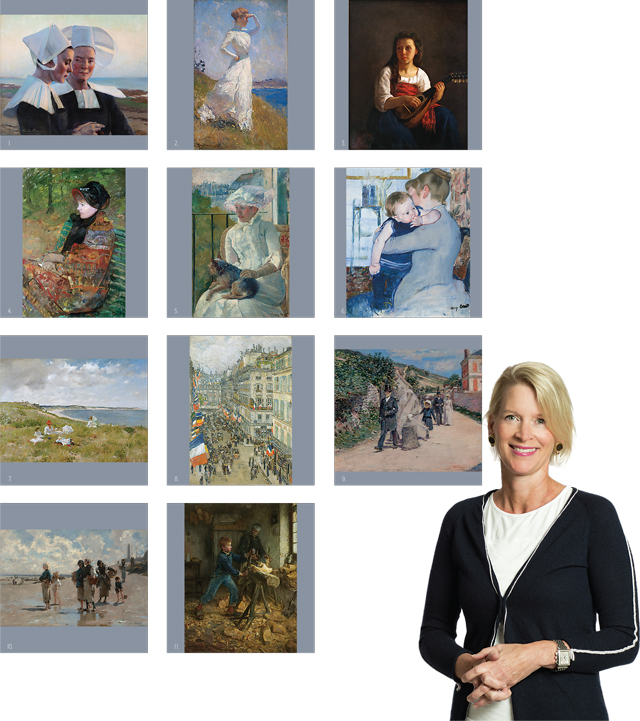

1. Twilight Confidences, 1888, Cecilia Beaux (American, 1855–1942), oil on canvas. Image courtesy Georgia Museum of Art

2. Sunlight, 1909, Frank Weston Benson (American, 1862–1951), oil on canvas. © The Frank W. Benson Trust

3. The Mandolin Player, 1868, Mary Cassatt (American, 1844–1926), oil on canvas. Private collection

4. Autumn, Portrait of Lydia Cassatt, 1880, Mary Cassatt (American, 1844–1926), oil on canvas. Agence Bulloz. © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY

5. Young Girl at a Window, ca. 1883–84, Mary Cassatt (American, 1844–1926), oil on canvas. Image courtesy National Gallery of Art/Open Access

6. Mother and Child, c. 1889, Mary Cassatt (American, 1844–1926), oil on canvas. Cincinnati Art Museum, Ohio: John J. Emery Fund/Bridgeman Images

7. Idle Hours, ca. 1894, William Merritt Chase (American, 1849–1916), oil on canvas. Courtesy Amon Carter Museum of Art, Fort Worth, Texas

8. July Fourteenth, Rue Daunou, 1910, Childe Hassam (American, 1859–1935), oil on canvas. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art/Open Access

9. The Wedding March, 1892, Theodore Robinson (American, 1852–1896), oil on canvas. Photography © Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago

10. Fishing for Oysters at Cancale, 1878, John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925), oil on canvas. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts Boston

11. The Young Sabot Maker, 1895, Henry Ossawa Tanner (American, 1859–1937), oil on canvas. Photo by Jamison Miller

A Special Opportunity for the Region

At the moment, VMFA is the only other museum in the country planning to host Whistler to Cassatt, which is surprising – and not. VMFA is the largest lender to the exhibition, providing twelve artworks, a reflection of the museum’s strong collection of American art. Rawles points to significant donations from the Gottwald family, James W. and Frances Gibson McGlothlin, and Harwood and Louise B. Cochrane as the underpinning of the museum’s American collection. “We have a leading collection of American art,” she says, “We have had such tremendously generous patrons.”

But there are significant costs associated with hosting a traveling exhibition, Rawles notes – everything from registering, preparing, and insuring the artworks prior to shipping, to designing the galleries and creating advertising and educational materials. Many museums aren’t in a financial position to undertake such a large show. “There’s fallout from the pandemic,” Rawles notes. “Exhibitions are very expensive.”

Connecting Families with Art

Celeste Fetta, VMFA’s director of education, says she hopes families will use Whistler to Cassatt as a jumping-off point for more activities and discussion. The exhibition will feature a family looking guide and downloadable resources, as well as coordinated painting classes focusing on en plein air (painting outdoors) and Impressionist techniques.

Fetta notes the state-supported museum falls under the purview of the state Department of Education and takes its charge seriously.

“Stimulating creativity is a goal,” she says. “We want to encourage people to find their inner artist and be inspired by these artists who were creative and innovative. We want people to find ways to express themselves and be encouraged with other skills they can apply: critical thinking, creative thinking, observation. Those are universal skills and applicable to what we all do.”

For children especially, Fetta says, art classes encourage concentration and drive home the point that it’s the process, not the product, that matters. “We’re not focused on every project looking the same,” she says. “Mary Cassatt didn’t turn out that work in five minutes; she studied. All those artists really had to work to get there, even in abstraction.”

Fetta notes that beyond classes, families are welcome on the first Sunday of every month to Open Studio, where a project – complete with all materials needed – is ready and available. Art cards at the Start Space on the main floor’s West Rock Art Education Center provide simple prompts to spark conversation.

All the VMFA’s education offerings are designed to welcome people where they are, Fetta says. “We want to make sure we’re giving space for visitors and participants to feel heard and valued,” she says. “We want a collaborative environment. We want the museum to feel like a place where people can come and feel welcomed and part of.”

Fetta says it’s gratifying to watch children start with classes at very young ages and then progress through their teen years. She recalls when one family, who participated faithfully in the annual gingerbread workshop, reached the point when their youngest child aged out of the program. “The parents wanted to do it one more time,” Fetta says. “The dad talked about how meaningful it was for them. It’s definitely a sustained relationship we build through these experiences.”

Curator Rawles agrees. “Aside from special exhibitions and the permanent collection, which is the pulse of the institution, we want people to come to the museum,” she says. “We want it to be [a public] playground. Come for thirty minutes or come for a full day. Sit in the park, or a restaurant, or stroll in the galleries. It’s a vibrant and inviting place.”

Photography: David Stover, Sandra Sellars