It only took a moment for Anne Moss Rogers’ life to change direction; only seconds for her to move from years of fear and dread to a life committed to service and education. That moment, when she learned her younger son, 20-year-old Charles, had died by suicide, was the most devastating moment of her life. But the heart-wrenching experience fueled her desire to help others.

Rogers and her husband were eating dinner in a restaurant on a Friday night – June 5, 2015 – when the Richmond police called. The call sent a shockwave through Rogers, who had been parenting Charles through issues of anxiety, depression, and drug use for several years. “It hit me that they were coming to say my child is dead,” she says. “I thought, This can’t be happening.”

Rogers immediately thought Charles died of an overdose, but the police told her he died by other means and that it was a suicide.

When you learn about a suicide, there can be a great deal of shock and disbelief. Often, the foretelling signs are buried in a personal darkness. Outwardly, Charles was not a teen people would expect to die by suicide. He was an effervescent child who people loved to be around. “He would scramble into my lap,” Rogers says. “He was a cuddlier child than his older brother.”

During his younger years, Charles was diagnosed with ADHD and delayed sleep phase syndrome (DSPS), causing a malfunction of the melatonin in his brain and keeping him awake until late into the night.

Both in and out of school, Charles was innovative, smart, and creative. He struggled with anxiety and depression, something he hid from others. He was “the funniest, most popular kid in school,” Rogers says. “Everyone loved him. He was entertaining and funny on the spot. I miss that almost as much as I miss his hugs.”

Rogers believes Charles started having thoughts of suicide when he was in the seventh grade. “His friends have said they would get texts from him at night with dark thoughts,” she says.

Around the age of fifteen, he tried beer and marijuana. “To him, doing drugs or alcohol at night when he was struggling with thoughts of suicide made sense,” Rogers says.

Then Charles began showing signs of depression and suicide ideation. He lost interest in the things he was passionate about such as joining clubs. He started taking risks and going to the doctor all the time, both signs of depression. But he never “pulled away or isolated himself,” Rogers says. “He was hyper-social.”

One counselor suggested the family put Charles in a wilderness therapy program where kids live in the wilderness with counselors for weeks at a time. “It’s something you do because you think your child’s life is at risk and you have no other choice,” Rogers says. “We had him kidnapped out of his bed. I will never forget his face as he went out. That is burned in my head.”

That was followed by two different boarding schools – one was a therapeutic boarding school. Within the first month of being home after twenty-two months away, Charles tried heroin and “it made him feel like a king,” Rogers says.

Charles went to detox in May 2015, right after he turned twenty. That was followed by rehab and a recovery house – where he relapsed within a day. He died by suicide within two weeks.

The Statistics

The statistics on teenage suicide tell an unnerving story. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the suicide rate among young people between the ages of ten and seventeen increased 70 percent from 2006 to 2019. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for 15- to 24-year-old Americans. The prevalence of suicidal thoughts (or ideation), suicidal planning, and suicide attempts is significantly higher among adults ages eighteen to twenty-nine than among adults thirty and older.

If there is any good news, it’s that the statistics on teen illicit drug use have gone down, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Based on the National Institutes of Health 2019 “Monitoring the Future” survey, there are continuing declines in prescription opioid misuse among teens and illicit drug use in teens. Oxycontin, for example, dropped significantly among twelfth graders over the past five years, with only 1.7 percent reporting in 2019. That is the lowest level of use since it was first measured in 2002 at 4.0 percent.

Devoted to Mental Wellness

Rogers began advocating for youth mental health five years before Charles died. Now the author and founder of the blog EmotionallyNaked.com, Rogers is a motivational speaker as well as a TEDx speaker who talks about preventing suicide, reducing substance misuse, and finding life after loss.

As a registered safeTALK trainer, Rogers presents training programs on suicide prevention. She conducts coping strategies workshops for school-age children and helps young people find ways to manage pain and face challenges.

A 10-year board member for Beacon Tree, an organization that advocates for youth mental health, Rogers is now working with Runway2Life, an organization focused on suicide prevention. She also works with the National Alliance of Mental Illness and will be speaking at the national American Foundation of Suicide Prevention Long Term Survivor of Suicide Loss conference in Ohio this summer. She is the 2019 YWCA Pat Asch Fellow and the first non-clinician ever invited to speak at the National Institute of Mental Health.

Rogers’ mission in all of her work is simple and heartfelt and comes from a place of empathy: Losing a child is painful and agonizing, and she doesn’t want any parent to experience that loss. She wants to help prevent teen suicide and also help parents find information and resources, something Rogers didn’t find until later in her journey.

The Ultimate Inspiration

Even though Rogers had been an advocate for mental wellness, her son’s death motivated her in a more compelling way. In 2016, she took the first step to a life devoted to preventing teen suicide and finding mental health solutions when she wrote a newspaper article for the Richmond Times-Dispatch. It took her five months to write the article. After she finished, she felt some relief and a sense of purpose.

After it was published, the digital version went viral and she received over 2,000 online comments from around the world. She took the time to read each and every comment because she knew each person had a tragic story to share.

She followed the article by launching EmotionallyNaked.com to share information and resources on suicide prevention, mental health, and grief. Since February 2016, her blog has reached close to a million readers. After writing the blog, she began to get requests for speaking engagements.

People who had gone through the same pain were trying to get in touch with her. Losing a child to suicide or addiction can be isolating. Rogers’ family suffered what she calls “the triple stigma.” Her son had suffered from depression, was addicted to heroin, and died by suicide.

“After the memorial services, some people treated the death as if I erased him from my family tree. They didn’t want to talk about him, and people would interrupt me if I was talking about him and try to divert the conversation to another, more comfortable subject – when what I really needed was to talk about my son,” she says. “I got the impression they didn’t want to talk to me because it’s uncomfortable being around someone who is hurting so much. They don’t know what to say. It’s so personal and everyone’s worst nightmare.”

Many people think of suicide as a choice, but Rogers says it’s a medical event we might think of as a “brain attack,” like we think of a heart attack. “A person struggling with thoughts of suicide has to have reached a point when they feel their capacity for emotional pain has outweighed the amount of time they’re able to wait for relief, at the same moment when they have access to the means to end their life. It’s a point where the instinct to survive loses. That instinct is strong and usually wins,” she says.

Launching the blog was a large part of her healing journey. “After the article for RTD went viral, other parents struggling who had lost a loved one to suicide or overdose found the blog and felt part of a movement,” she says. “I want to talk about it because my son said things that would indicate intention. But I didn’t recognize the signs.”

Giving back is also part of her healing journey. “I understood early that I needed to face the pain and allow it in because no feeling is permanent. It would lift eventually,” she says. “And by writing my way through it, I found healing.”

Positive Feedback and More Words

Rogers receives feedback on social media from teens and parents offering thanks and hope. One mother wrote to her about her 16-year-old son who was battling addiction after she saw a Google search on his phone for “painless ways to commit suicide.” Roger says the mother who reached out was a social worker experienced in working with suicidal individuals; she knew to put away sharp objects, safely secure guns, and hide pills. Knowing what to do, however, didn’t take away this mother’s fear and pain. None of her friends knew what to say to her, and it was hard for her to put her feelings into words. But she would always come back to Rogers’ blog and her experiences with Charles. She told Rogers that their connection offered her relief.

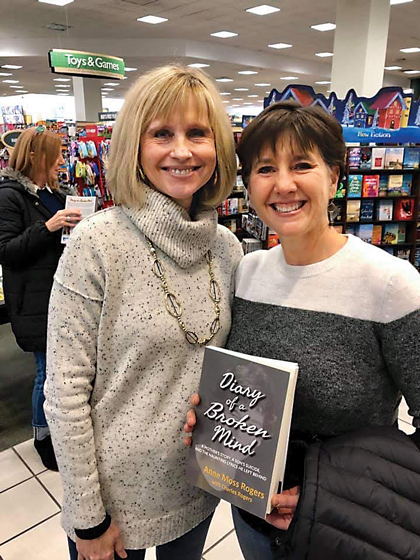

With the success of the article and blog, Rogers was inspired to write a book, and last year, her book was published. The process of writing Diary of a Broken Mind: A Mother’s Story, A Son’s Suicide, and the Haunting Lyrics He Left Behind was not only a way for her to heal, but also a way to help others. She couldn’t write about her son’s addiction and depression when he was alive for fear it would hurt him. But after his death, she decided not to hold back.

“My son had shown the classic signs of suicide and I didn’t know because I was uneducated. No one talked about it,” she says. “Therapists never said he might be at risk, although some of the testing probably indicated he was. But we don’t talk about it. So those suffering feel shame and don’t reach out. And parents like me don’t know the often subtle signs of suicide, so we miss an opportunity to prevent it.”

Recognizing the Signs

Rogers realizes now that she missed some of the signs of suicide when Charles was struggling. “My own son left tweets and clues of classic suicidal thinking, and I didn’t recognize those signs,” she says.

When Charles tweeted, If I died, no one would notice for 30 days, she realized later it was a cry for help. Rogers didn’t see the tweet because her son had blocked her from his social media account. Rogers says, “Some thought it was a joke. Others felt awkward. Still others commented that it was not the case.”

When someone sent her a screenshot of the tweet, she took it to mean he had hit rock bottom from his addiction and was going to ask for help. But his rock bottom was suicide,” she says. Today, she advises families to do whatever is necessary to keep the lines of communication open. “Don’t buy the rock bottom or tough love myths. No one knows what that really means.”

Talk About Suicide

Rogers stresses the importance of talking to children about suicide. While some people believe talking about suicide can cause a teen to take action, findings by the National Center for Biotechnology Information suggest that acknowledging and talking about suicide may in fact reduce, rather than increase suicidal ideation, and may lead to improvements in mental health in treatment-seeking populations.

Rogers recalled how a mother had brought her son to one of her speaking engagements. The woman was shocked that Rogers talked so openly about Charles’ suicide.

“As she [the mom] got in the car still fuming, her son turned to her and said, ‘Mom, there’s something I need to tell you. I have been thinking of suicide. I have a gun,’” Rogers says. Later, the woman emailed Rogers to tell her how she had secured the gun and to thank her for helping save her son’s life.

According to Rogers, 85 percent of those who die by suicide leave some indication of their intentions before they die. “We know from studies that people don’t want to die; they just want to end the pain,” she says. “People actually leave invitations for people to ask about it [suicide]. But we’re uneducated and don’t know what these are.”

At the General Assembly

Rogers is also an advocate for suicide prevention and mental wellness policy. At the first session of the 2020 Virginia General Assembly, she testified in support of two bills.

The first, HB 1063, would abolish suicide as a crime in Virginia. “Suicide is a death of despair and a public health issue that is often the result of mental illness, physical illness, trauma, or adverse personal circumstances,” Rogers says. “Depression and suicide are public health issues, not crimes.”

Suicide as a crime is an “antiquated, stigmatizing, and outdated law from the 1400s England,” she says. “Criminalizing serves as an impediment to those seeking help.”

The second bill, HB 928, would create a pilot addiction recovery school for Virginia serving thirteen counties. The school would teach kids struggling with drug and alcohol addiction and “gives them a chance to pursue recovery, get their education, and have support that has a more successful outcome,” Rogers says.

A change in policy has always been shown to influence behavior, and Rogers hopes these new bills will be a good first step for Virginia families. “When you get rid of the law of suicide, you remove the stigma and position it as a public issue,” she says. “If you establish a recovery school, you are sending the message that the health of our youth is worth investing in.” (Both bills were still under consideration at press time.)

All of her work giving back has helped Rogers heal emotionally and “move forward again,” she says. “Ultimately, I want to help other parents avoid having to go through what we have been through.”

Photo: Tasha Tolliver