Imagine the problems of a typical suburban teen: Calculus test? Girlfriend issues? Not sure what to wear to prom?

Most people don’t picture heroin addiction.

I would say that we’re just a normal family,” said Henrico County mom Jenny Derr. “I was room parent for my kids, on the PTA board, and we sat down and ate dinner together every night.”

But the model family was shattered when they learned their son, Billy, a popular student at Mills Godwin High School, was addicted to drugs. After struggling for several years to stay sober and kick the addiction, Billy passed away from an overdose on April 12, 2016.

Billy Derr’s addiction wasn’t an isolated problem.

“Just a few weeks into my term, I learned what too many parents already know: We have a (prescription opioid) problem,” Virginia Attorney General Mark Herring told a group of concerned citizens at an event at Godwin. “There is no typical heroin or opioid abuser. It can touch every one of us. The numbers don’t seem real, they’re so large.”

The disease of addiction doesn’t discriminate, said Honesty Liller, CEO of the McShin Foundation, a Virginia nonprofit that supports substance users and families. Liller, who’s been sober for more than ten years, began using drugs at age twelve, discovered heroin at seventeen, overdosed and was brought back with naloxone (a prescription medicine that reverses the effects of an overdose), relapsed, and finally found a treatment that worked. She and her husband are raising their two kids in a substance-free environment. “We don’t sugarcoat stuff here,” says Liller. “This is life and death.”

Statistics are Shocking

Because drug addiction can easily seem like a disease that doesn’t happen to families like ours, many people gloss over the multitude of news stories about the rise of opioid and heroin use. Perhaps it’s easier to believe it’s happening more in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities and regions like Appalachia and the Rust Belt. Indeed, the media has covered drug use and abuse heavily in recent years – and with good reason.

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse:

• Half of young people who used heroin got started by abusing prescription opioids.

• The number of opioid prescriptions nearly tripled over the last twenty-five years, and the United States now accounts for nearly 100 percent of the world’s hydrocodone prescriptions and 81 percent for oxycodone.

• The number of Americans abusing heroin nearly doubled from 2007 to 2012, with nearly 700,000 now abusing heroin.

In Virginia, abuse and overdose deaths continue to rise:

• Prescription opioid overdose deaths rose 44 percent between 2007 and 2015.

• Heroin overdose deaths rose more than 600 percent between 2010 and 2015.

• Fentanyl deaths rose 367 percent from 2007 to 2015.

• More than 500 people went to an emergency room from a heroin overdose in the first four months of 2016, a 250 percent increase over 2015.

Each of those statistics has a name, a face, and a family.

“My son, Dawson, was such a happy baby,” said Laurie Pettit. “He loved school, his friends, his pets, and his family. Dawson played Little League baseball, YMCA basketball, travel soccer, and he was a brown belt in karate. He later played lacrosse, and tennis and golf through high school.”

The good student and multi-sport athlete from a good neighborhood died three years ago of a heroin overdose in the bathroom of a local grocery store.

Pettit suspected Dawson smoked pot in high school and tried to investigate that usage. “I thought I was wise about drug use because I was nosy, and I was trying to be in my adult son’s life. I recognized some potential drug use,” she recalled. “But when the word ‘heroin’ was used, you could have knocked me over with a feather.”

Dawson struggled with drug addiction for several years and had been, by all accounts, in recovery when he relapsed and overdosed.

To many, it seems illogical that a healthy, happy kid could transform into a heroin addict. But scientists – and parents – see it all too often, and it’s surprisingly easy to do.

Derr believes Billy’s addiction may have been triggered by prescription medication he received after a car accident.

“It can start in your medicine cabinet,” said Valerie Murphy, grant coordinator at Chesterfield SAFE, an organization that works to prevent and reduce substance abuse. SAFE research shows kids as young as middle-school-age are misusing prescription drugs, particularly painkillers or ADHD medication. And many young people mistakenly believe that if it’s a legal substance, it must be okay. But then they can’t stop using.

“So many people say they never thought they’d use a needle, but after a while, that was the only way to get a high,” Murphy said. “Addiction turns from trying to get high and trying to get the euphoria, to trying not to get sick. You want the drug just so you don’t go through withdrawal, because that’s very painful.”

Derr understands. “In my opinion, it starts with over-prescription of narcotics – getting your wisdom teeth removed, sports injuries like broken arms. And these kids are getting 30-day supplies of Percocet they don’t need. They might need it a day or two, but most times, a Tylenol is okay. But parents don’t know,” said Derr. “They didn’t go to medical school. They get the prescription and they fill it, and after a couple days, a lot of these kids are off and running. Sometimes it’s that quick if it triggers a disease in your brain,” says Derr. “By the time we realized Billy had a drug problem, he was a full-blown addict.”

The Science of Addiction

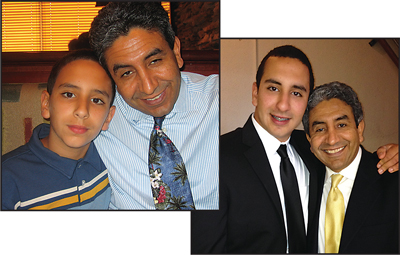

Omar Abubaker, MD, PhD, chair of oral and maxillofacial surgery at Virginia Commonwealth University, is an expert on pain management after surgery. Sadly, he’s also a parent who could not save his son, Adam, from addiction and an overdose on Sept. 30, 2014. After Adam’s death, Dr. Abubaker turned his energy to learning everything he could about addiction, drawing attention to the problem and advocating for treatment options.

Some families, he said, are more susceptible to substance-use disorders, whether that’s tobacco, alcohol, or drugs. “What I’ve learned – from the science, not just my experience – is that addiction is 60 percent genetic and 40 percent environmental. And I used to believe that if it’s genetics, it’s going to come up. But what surprised me was that the environment could control the genetics early on. If you have the predisposition but a favorable environment, you can override it,” Dr. Abubaker explained. “If you look at some cultures that don’t have drugs and alcohol readily available, addiction is not as prevalent.”

But opioids are widely available in the United States, especially to teens. According to a study published recently in the Journal of the American Medical Association -– Psychiatry, heroin use, long believed a problem of teens in poor urban areas, is now more common in middle-class suburbs. Most addicts today are white, wealthy, and do not live in cities, the study said, and most addiction cases are likely linked to the increasing availability of prescription opioids. Of nearly 2,800 heroin users surveyed, more than 75 percent said their first experience was through prescription painkillers.But

heroin, at about five dollars a hit, is considerably cheaper.

Why are opioids so widely available? A generation ago, patients who had routine procedures like wisdom teeth removal were given Tylenol. Today, however, several things have changed: big pharmaceutical companies wield a lot of power; the Joint Commission (a nonprofit organization that accredits health care organizations) requires certain standards for pain management; and physician pay is often connected to patient satisfaction scores (conceivably, a patient who doesn’t feel his pain is being managed correctly could complain).

In addition to painkillers being offered too often, says Dr. Abubaker, they’re being offered to those who aren’t prepared to know how to use them. “The part of the brain that controls judgment… does not fully develop until ages twenty-one to twenty-four, especially for boys. Yet all other aspects of the human brain are developed.”

And so, he says, the responsibility to be the judge of a young person’s decisions must revert to the parents. “I wanted to be a liberal father, and I thought my instructions would be enough. But I believe you have to take an active role in the decisions of children until they’re older.”

Many parents today have begun questioning prescriptions, said Dr. Abubaker, and that’s a good thing, as a lot of patients are fine with an over-the-counter painkiller. “In fact, I’m seeing that parents are more willing to change than the doctors are.”

A Chronic Disease

“To the people who don’t understand addiction, he may be just another kid who made a bad choice,” read Billy Derr’s obituary in the Richmond Times-Dispatch. “For those who do understand the disease, this was our oldest child, a brother, a friend, and as his mother, my children are my everything. The disease of addiction is non-discriminatory and without mercy. It is up to us to open our minds and hearts to those suffering from the disease.”

Even with all the media attention and the reality that nearly everyone knows someone – a friend’s child, family member, neighbor – with a problem, there is a stigma associated with addiction. In the past, those with a substance use problem were considered weak or even immoral. But scientists now believe that addiction is a chronic disease that takes over the brain. And needs to be managed as such.

Nobody chooses to be an addict, says McShin’s Liller, who notes that most kids who try marijuana or alcohol aren’t going to get hooked, but you don’t know until it’s too late, and then it’s harder to stop than to keep going.

Kids are clever and resourceful at finding drugs. They’re in every school and in many other places, too, says Liller. One Lynchburg family learned too late that their son was receiving fentanyl and other drugs from overseas through the mail.

What Can You Do?

Just as the problem is not simple, there’s no easy solution.

The first step is to be aware that your child is exposed to drugs, whether or not he or she tries them. “There are countless lists of warning signs of drug use,” said Liller, who recommended drugrehab.org specifically.

Parents need to recognize what kind of example they’re setting for their children. While drinking may not seem like a big deal to some adults, children may see the behavior as permission to do the same. “We always think that marijuana is the gateway drug,” said Dr. Abubaker. “I think that’s false; I think alcohol is the gateway drug. I would recommend not drinking in front of your child. It sounds like a sacrifice to make, but … for the pain you go through, no sacrifice is too much. It’s less painful not to drink in front of the kids than to go through what I went through. If I had it to do over again, I would plug every possible hole that would have led me to have the experience I had.”

Most area school systems have programs to educate kids and parents about the dangers of substance use. But, noted Pettit, those programs often don’t reach families in time. “My advice to parents is to show up for these things. Unfortunately, people still have that attitude that ‘it’s not my child,’ or you’re worried about what the neighbors might think.”

And, she observed, “Children are programmed not to share with parents if they are having issues with bullying or self-esteem, or with school in general. They’re not sharing that with parents because they want everything to go along smoothly and want parents to think they’re living the dream,” Pettit continued. “But they’re struggling, and they turn to drugs to feel normal.”

It’s important to start talking about drugs early, said Derr. “I think education needs to start in middle school. We didn’t know it at the time, but we later found out that Billy had started drinking and smoking weed in the eighth grade. We had no idea, and we were an involved, close-knit family. By the time we realized he had a problem, it was the start of his senior year of high school.”

Derr said parents should always keep all prescription medicine locked up. Noting that ADHD medications like Adderall are commonly abused, she agrees with Dr. Abubaker about staying on top of medications and counsels parents to supervise their child’s prescriptions. “We thought we were instilling responsibility by having Billy take his medication. If I had it to do over again, I would do things differently.”

And if you suspect anything, said Liller, seek help immediately. “Don’t wait. I’ve seen kids die because parents were hoping the problem would just go away.”

One Path to Recovery

Many parents become frustrated with a child who’s lying and even stealing to support a drug habit. Some feel they must sever contact until a child sobers up, and that’s understandable, said Liller. But family support can be crucial to recovery. The first stage is detoxification and medically managed withdrawal. Detox, even with chemical assistance and lots of professional help, is a brutal process. “Going through detox is twenty times worse than having the worst flu,” said Liller. “You really want to die.” Recovery is an hour-by-hour thing. And relapses are all too common.

Most recovering addicts end up in a residential treatment program where they can receive group and individual counseling.

Because many people finance their substance use by turning to crime, some localities have recognized the need to support them with drug courts that assist non-violent felons recovering from addiction.

Those who have been affected by the disease of addiction say expanding treatment options is as important as prevention. The McShin Foundation offers housing for people over age eighteen who are undergoing treatment programs.

For teens, the McShin Foundation and St. Joseph’s Villa recently teamed up to expand the McShin Academy, a recovery high school now located on the Villa campus on Brook Road. The school combines a full educational curriculum with counseling and support services for teens addressing substance abuse and addiction.

To control the supply side, government and medical professionals also are stepping up. Various government agencies have called for more stringent prescribing of opioids, and Virginia’s Pharmacy Monitoring Program has curbed the doc shopping that some patients engage in to get multiple prescriptions. Attorney General Herring has made solving the opioid and heroin problem a centerpiece of his time in office.

Not One More

For some parents, it’s coming too late. But they hope by sharing their experiences, they’ll wake up others to the issue and save lives.

“My mantra became, ‘Not one more, not one more,’” said Pettit. “All I can tell you [today] is that receiving this news is like getting blindsided, run over by a freight train, and hit in the stomach with a two-by-four,” she wrote in an essay about her experience. “Maybe all three of those at the same time. It is the most physical pain I have ever experienced in my life, and I miss Dawson more today than I did on March 1, 2014. I miss his smile, his laugh, his sense of humor, his crazy vocabulary, and his nicknames for everybody and everything. But mostly, I miss his whole lotta lost potential.”

Resources

There are many resources to help families in Central Virginia. If you’re not sure where to start, you can ask for recommendations at your child’s school.

The McShin Foundation

804-249-1845

mcshin.org

Family Counseling Center for Recovery (FCCR)

Richmond: 804-354-1996

Midlothian: 804-419-0492

fccr-va.com/about-fccr-richmond-va

SAARA of Virginia, Inc.

804-762-4445

saara.org

Richmond Behavioral Health Authority

804-819-4000

rbha.org

Chesterfield Mental Health Services

24-hour crisis line: 804-748-6356

chesterfield.gov/mhss

Henrico Mental Health & Development Services

804-727-8500

henrico.us/mhds

Hanover County Community Services Board

804-365-4238

www.hanovercounty.gov/358/Community-Services-Board

Chesterfield SAFE

804-796-7100

chesterfieldsafe.org

photos: Joe LaPaille, Joe Mahoney