Ten years ago, Cathy Motley-Fitch gave birth to premature twins – a son, Grayson, and daughter, Lola. Both babies were tiny, but healthy. But just over a week later, Cathy stood in the neonatal intensive care unit holding her daughter close as the infant took her last breath. Lola didn’t die from a fatal condition. Her death was the result of misdiagnosis and medical errors.

Medical errors are the third leading cause of death in the United States. A medical error is a preventable adverse effect of care. This might include an inaccurate or incomplete diagnosis or treatment of a disease, injury, infection, or other ailment. “This is a common thing that happens in our nation, which is a very scary fact,” says Cathy. “We found about seven medical errors that led to Lola’s death. We don’t place blame on any one person. It happens at the best hospitals and at the worst.”

Cathy delivered the twins at VCU Medical Center on May 29, 2009. They were six weeks premature, born at thirty-two weeks. Lola weighed three pounds five ounces, and Grayson was two ounces heavier.

Cathy delivered the twins at VCU Medical Center on May 29, 2009. They were six weeks premature, born at thirty-two weeks. Lola weighed three pounds five ounces, and Grayson was two ounces heavier.

The babies were doing well with no complications. “They were called ‘feeders and growers’ in the NICU,” Cathy says. “Everything checked out fine.”

Cathy stayed at the hospital with the twins for a week until the staff suggested she go home and rest. Her husband, Alan, who worked at the same hospital as an orthopedic physician’s assistant, was ready to check on them during the day. “I made sure Alan would be at the hospital first thing in the morning for rounds,” Cathy says. “He worked one floor below the NICU.”

A day-and-a-half later, Cathy learned there was some concern about Lola. Her heart rate had dropped some, but Cathy was told she would be okay. She called the hospital several times during the day and evening and was reassured Lola was fine. When she called at ten to say goodnight, she was told Lola was feeling “punky and they had intubated her [put a breathing tube into the trachea to help her breathe],” Cathy says. “I asked Alan about it, and we jumped in the car and flew to the hospital. We were shocked at the appearance of our daughter. It wasn’t what Alan saw just hours before. Within six hours, she was gone.”

Chasing Answers

The couple was devastated. Cathy and Alan handled their emotions differently. “I spent days and nights going through Lola’s charts,” Cathy says. “I convinced Alan to look at them, and he was shocked at what he found.”They discovered Lola’s death was caused by misdiagnosis and a series of medical errors. “This is a place we trusted,” Cathy says. “If it could happen here, it could happen to anyone anywhere. Alan worked where it happened, and still works at VCU Health System – and believes in it.”

Cathy says Lola’s death had been reported as a typical death. The administration at VCU Health “didn’t realize it was caused by mistakes. When they found out, they embraced us and grieved with us,” Cathy says.

Ralph R. Clark, MD, the health system’s chief medical officer then and now, met with Cathy and Alan after Lola’s death. “Obviously, it was a very emotional time for them,” he says. “Despite their loss, they didn’t want to see people punished or dragged through a negative process. They didn’t want to blame or shame people. They wanted a different pathway.”

What the Mechanicsville couple wanted was to help prevent this type of tragedy from happening again. “Alan and I decided to unite and focus on how we could do good in the world. If we focused on our grief, we would drown,” Cathy says. “The grief and anger were destroying us. We were loving and raising one child while we were grieving the loss of the other child at the same time.”

Speaking Up for Lola

Cathy and Alan spoke with representatives from VCU Health and explained that they wanted to be part of preventing medical errors – between 240,000 and 480,000 medical errors occur annually in the U.S. – and bringing change to the system. “VCU Health said we needed to share our story, especially at their hospital,” Cathy says.

VCU Health asked Cathy and Alan to come and talk to medical students and residents. In 2016, the couple presented their talk in conjunction with the Virginia Hospital Healthcare Association’s Patient Safety Summit. “Their story was one of the personal stories told,” Dr. Clark says. “It helped to reinforce the purpose of the conference.” Today, Cathy and Alan, who are parents to 9-year-old Grayson and 7-year-old Sawyer Graham, speak to healthcare institutions around the country about their family’s story, hoping to prompt providers to listen and communicate. They have presented at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Duke University Hospital in North Carolina, George Washington University in Washington, D.C., Carle Foundation Hospital in Illinois, and Stony Brook University Hospital in New York, among others. “This has given Lola’s life a purpose. It has touched thousands of people,” Cathy says. “Of course, I wish she were here, but perhaps she was meant to be something bigger than just being in my arms. We are making sure the healthcare system is safe for our sons and charging healthcare professionals to be more mindful and thoughtful in the care they give.”

In their presentation, Cathy and Alan talk about communication, teamwork, empathy, and the decision-making that happens when patient care is taken to the next level. They talk about the errors that were made, as well as how to “speak to families who experience loss,” Cathy says. “We talk about transparency in hospitals, and how doctors can apologize. Once we heard those words, it turned our grief to motivation for change.”

In their presentation, Cathy and Alan talk about communication, teamwork, empathy, and the decision-making that happens when patient care is taken to the next level. They talk about the errors that were made, as well as how to “speak to families who experience loss,” Cathy says. “We talk about transparency in hospitals, and how doctors can apologize. Once we heard those words, it turned our grief to motivation for change.”

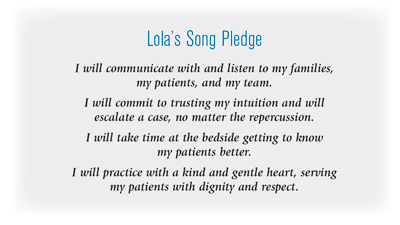

Cathy and Alan created a website, lolassong.com, and a pledge for healthcare professionals. “I wanted to make sure people were making a difference,” Cathy says. “I created a pledge based on what I thought was lacking in Lola’s care and what I needed.”

The couple’s goal is to have healthcare providers commit to communicating with and listening to their team members and to families they serve. “We want them to take time with patients, get to know them better, and serve them with respect,” Cathy says.

To date, more than 700 health professionals have signed the pledge online. Many have left comments. “The feedback we’ve had is that this changed the way they will practice,” Cathy says. “It inspires them to practice safer and take more time. They have said that Lola’s story has changed their lives.”

Harnessing the Power of Music

A Richmond native and trained vocalist with a bachelor of music degree from VCU School of the Arts, Cathy has relied on singing to uplift her, both personally and professionally.

But after Lola’s death, she stopped singing for six months. “I couldn’t sing or hear music at all. Something that had brought me so much joy, I couldn’t do,” she says. “As I worked through the grief, I was able to teach vocal lessons and start speaking on Lola’s behalf. Alan and I felt like that was our responsibility.”

Because of her training, Cathy found the ability to respond to the tragedy in her life by sharing Lola’s story in front of groups of people. “I was able to get up and speak about it,” she says. “This is our way to heal.”

Cathy wanted to use the power of music and communication in another way: to strengthen the skills – from communication to problem-solving – healthcare providers rely on when treating patients. Through that vision, she created Lola’s Song Project, which combines music and medicine.

“As a singer, I realized we often use songs – like Staying Alive for CPR – to help people remember the message. For Lola’s Song, providers would create a song, choosing whatever error they wanted to correct,” Cathy says. “They come from different disciplines, so they have to learn to work together. It teaches teamwork. Changing the words to songs also teaches emotional intelligence and effective communication through music.”

The faculty at University of Virginia Health System wanted to debut the project after hearing Cathy and Alan’s story. Tracey Hoke, MD, pediatrician and chief of quality and performance improvement at University of Virginia Health System, explained how Cathy initially pitched her the program. “Cathy said, “Dr. Hoke, I am going to tell you my crazy idea. Because of my experience teaching children and adults in the venue of music, I might be able to come up with an idea to teach the principles supporting good interactions with patients and families in a new way,’” says Dr. Hoke. “I thought it was a great idea. It was new and interactive and even fun. I was thankful that she was willing to think this way. This way, providers would take it with them as lasting lessons, not just an anecdote.”

Dr. Hoke identified a group – the NICU at the UVA hospital – that would pilot the idea. About thirty people participated. “It was powerful for the team,” she says. “The impact of families telling stories is important, but it’s fleeting nowadays because there are so many stories. This is a chance to hear a story and participate in a tangible exercise [singing the songs] to develop a new practice style or awareness of ways in which communications can go wrong.”

Through Cathy’s innovative project, participants used a simple tune they would remember and turned it into a tool they could use during an interaction at the hospital. “That was the magic,” says Dr. Hoke. “If Cathy had not been a trained singer and teacher, the conversation might have ended there. She had the wherewithal to imagine this project, and the strength to carry it out with a team of medical professionals. It was amazing.”

Changing for the Better

At a recent engagement, someone asked Cathy and Alan about their level of confidence in the healthcare system now. “Our confidence level rises when we see the number of pledges taken after we speak. It rises when someone says, ‘This story should be told to every healthcare professional in the nation,’” Cathy says.

VCU was transparent and embraced the couple when the mistakes were discovered. “They asked us, ‘What can we do to be better?’” Cathy says. “We were so impressed by their response.”

VCU was transparent and embraced the couple when the mistakes were discovered. “They asked us, ‘What can we do to be better?’” Cathy says. “We were so impressed by their response.”

Over the last twelve years – starting before Lola’s story began – there has been a significant change in healthcare at VCU and how patient safety is addressed. VCU brought in experts from outside industries to help providers understand the principles of high reliability, teamwork, and communication. “We have made some pretty good progress in safety and reliability,” Dr. Clark says. “We constantly work to improve working together in teams.”

The doctor says if anyone on the hospital team sees something they feel is wrong, they should feel comfortable speaking up and raising those concerns. Eliminating medical mistakes is a “lifetime of work,” he adds. “You have to work continuously to get better at it, and we are constantly striving to improve.”

Heartbreaking stories like Cathy and Alan’s stick with people. “They capture the heart and mind and help align the focus,” Dr. Clark says. “It makes the why evident. When you personalize something with a story, people take that away with them. It doesn’t escape your memory quite as quickly as a statistic might.”

Cathy and Alan are “amazing people to have gone through what they have experienced and turn that into something positive. It speaks volumes about their character,” he adds. “It’s a privilege to know them and walk alongside them. You never want to meet people this way, but the least you can do is be there with them wherever their journey goes.”

Helping Others Find Their Voice

Cathy Motley-Fitch takes a holistic approach to teaching voice. “I’m acutely aware of how people are holding themselves and how to help them project their voice,” says Cathy, a former fitness trainer. “I started to combine fitness with my voice work, so people realize that how they hold their body affects the sound that comes out of their throat.”

She has had to use that concept in speaking to groups about Lola and preventable medical errors. What she has learned through Lola’s tragedy and her subsequent presentations is something she wants to share with others. That’s why Cathy launched FitVoice last year.

“I teach college-age students and highly accomplished women in the corporate world how to speak better, improve their voices, build their confidence, and to affect an audience,” she says.

Her work focuses on mindset and self-confidence. “We talk about the way you think about yourself and how others perceive you,” she says. “We talk about stance and posturing. The way we speak is the way we are perceived.”

Women can be at a disadvantage when it comes to being heard. “This makes women take the time to think about how they are perceived. It’s not always what you say, but how you say it that dictates a response from those around you,” Cathy says.

Hallie Hovey-Murray, a third year law school student at William & Mary and the current Miss Commonwealth who will be competing for Miss Virginia in June, started working with Cathy a year ago. “I’m a ventriloquist, and we do work on the vocal and breathing aspect of performance,” she says. “It’s really helped me take my talent preparation to the next level. Her program helps in so many facets of my life.”

Cathy’s life now is on a journey she never anticipated. “Lola’s death was a tragedy I would never want anyone else to endure,” she says. “I could never have imagined that being able to embrace what happened to us has let us have a very happy life with our two sons and our dog, Charlie. It has enabled me to use my voice in ways I never thought I could. I am not only sharing my daughter’s story, but also my story in helping people use their voices.”