Virtuoso Charles Overton didn’t find the harp.

It found him.

It’s such a warm instrument. You can feel the vibrations as you play. They reverberate through you,” says the talented 23-year-old, explaining his interest in the harp. “It’s one of the few instruments where you have direct contact and control over the sound you’re making. I think that’s liberating. It’s very special.”

The world is taking note of Charles’ musical gift. Since taking up the harp at age nine, he has played in prestigious venues around the world such as the Salle Gaveau in Paris and Carnegie Hall’s Weill Recital Hall, as well as concert halls including the Berlin Philharmonic, Tokyo’s Suntory Hall, and Boston’s Symphony Hall. At first, he traveled with the Richmond-based American Youth Harp Ensemble. Since his days in Richmond, he has toured with various ensembles or with his own jazz group, the Charles Overton Group. In 2013, he was a finalist at the American Harp Society National Competition.

Accomplished in classical, world, and jazz music, Charles is becoming known for his improvisational jazz stylings. “There are fewer than ten jazz harpists in the world,” says Dr. Bill Banfield, composer, guitarist, author, and professor of music at Berklee College of Music in Boston. Banfield also owns JazzUrbane Recordings, and Charles is an artist on his label. “Charles is a virtuoso. He has a voice on the instrument, and that’s one of the things you look for with young artists. He projects a very unique voice, which makes him special.”

Musical from the Beginning

Lisa Moreland Overton noticed her son’s proclivity toward music when he was a baby. Most babies are comforted by pacifiers and blankets when they get fussy, but Charles was always comforted by music. “He would listen to the same Mickey Mouse tape over and over,” says Lisa, who works in pharmaceutical sales at Merck in the oncology division.

By the time he was eighteen months old, his mom says he was watching – and actually paying attention to – Disney’s animated classic Fantasia. In order to continue to foster his love of music, his mother enrolled him in a Kindermusik class in Winchester, where the family was living at the time. “When he was about two, his Kindermusik teacher said he would benefit from getting into some kind of music lessons,” Lisa says. “We wanted to see what instruments he was drawn to.”

He picked up the violin at a musical fair, so Lisa and her husband, Cedric, lined up a violin teacher, and Charles began private lessons in the Suzuki method, a Japanese method of instruction that views music as a principal language. He was two-and-a-half. His parents continued his lessons after the family moved to Glen Allen in December 1997. From the get-go, his teachers were impressed by his abilities.

“I saw a natural talent in him,” says violinist Françoise Moquin, who gave him lessons in 2003 when he was eight. “He could understand things quickly. He was always wanting more and more intensive music.”

During that time, Charles played with the Richmond Symphony Youth Orchestra and participated in Richmond Ballet’s Minds in Motion program. He also played basketball, tennis, ice hockey, and soccer. “I even took up snowboarding for a couple of years,” he says. “I was really into all that stuff. But when harp entered my life, I wanted to focus on that. I love it.”

During that time, Charles played with the Richmond Symphony Youth Orchestra and participated in Richmond Ballet’s Minds in Motion program. He also played basketball, tennis, ice hockey, and soccer. “I even took up snowboarding for a couple of years,” he says. “I was really into all that stuff. But when harp entered my life, I wanted to focus on that. I love it.”

He decided to give up ice hockey because the time schedule didn’t fit in with his harp classes. “The hockey schedule was a problem,” his mom says, “but he still played soccer with the YMCA and took tennis lessons.”

Lynnelle Ediger noticed the youngster’s talent when he was attending Richmond Montessori School where she served as the school’s music teacher. The founder of the Academy of Music (now GreenSpring International Academy of Music) and the American Youth Harp Ensemble, Ediger had a hand in introducing Charles to the harp when he was nine.

“I said to Charles, ‘You need to play the harp. Go home and tell your mom you want to play the harp,’” she recalls.

Even though he liked playing the violin, Charles wasn’t sold on just one instrument. After talking with Ediger, he went home and told his mom he wanted to play the harp. “I consulted with Françoise, and she said he could do both simultaneously,” Lisa recalls, noting that for the next two years, her son studied both the harp and violin.

Charles was eager to take advantage of all the classes and travel opportunities offered by the Academy of Music and the American Youth Harp Ensemble, but he and his parents knew it would be difficult to incorporate intensive training into his school schedule. After talking about the options, his parents decided homeschooling was the answer. That helped pave the way for greater opportunities.

“The Harp Ensemble element of touring showed me music was more than just something you do as a kid,” Charles says. “It could be a career option. I viewed music differently because of Lynnelle. She was a great teacher.”

Ediger saw Charles’ potential early on. “He had perfect pitch and he was extraordinarily musical,” she says. “What really stood out was that he had exceptional talent, but was also curious, as well as a conscientious hard worker. He was always interested in learning more. He was a student who really understood the importance of disciplined and dedicated practice and coming prepared. He showed signs of greatness.”

Charles traveled as part of the American Youth Harp Ensemble to Paris in 2006 to perform in the Salle Gaveau with American gospel singer Liz McComb. “We recorded an album with her, and Charles was part of that recording,” Ediger says. “The year before, in 2005, I took him as part of the Ensemble on tour to Italy and he performed all over Italy.”

In 2007, the Ensemble performed in Carnegie Hall and received two standing ovations. For the third encore, Ediger sent Charles out as a soloist to perform a jazz piece. “I told him it was time for him to shine. It was an electrifying performance, and the audience gave him a standing ovation,” she says. “Afterward, I told his mom a star has been born. I am really proud of him.”

Learning Independence

The summer he turned fourteen in 2008, Charles participated in Boston University Tanglewood Institute, a program of the Boston University College of Fine Arts and affiliated with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and Tanglewood Music Center. “That was a defining moment,” he says. “The experience I had there told me, I have to do this all the time. I want to do this all the time.”

It was there he learned about the concept of a boarding school for the arts. “I wanted to be in a similar environment, surrounded by musicians,” he says.

He and his parents investigated several boarding schools before Charles settled on Interlochen Arts Academy in northern Michigan. “I chose Interlochen because of [harpist] Joan Holland. I took a trial lesson with her in May 2009, and during the lesson, I had never heard anyone talk about the harp the way she did,” he says.

Holland was the first person to explain how your body is involved in playing a harp and that it was important to think about how your body feels when you are playing. “It’s about approaching the instrument from a relaxed position and that will create the best sound,” he says. “I hadn’t heard that before. Her ideas about harp technique were different. They were beneficial for me.”

Before enrolling at Interlochen, Charles’ father called a family meeting. “It was a big commitment for him to go to boarding school,” says his dad, Cedric, who works as a general manager at the Quantico MCX and had enjoyed bonding with his son while driving him to commitments in and around Richmond. “I had more apprehension than he and his mother did. It was one of the first prolonged family chats we had. We talked about the pros and cons, but ultimately, I saw his commitment. It was better for him in order to progress in his career. Originally, I reluctantly agreed, but when I saw his passion, I signed on.”

Going away to Interlochen helped Charles “forge the way for independence,” his mom says, and gave him what he “needed in order to pursue what he is pursuing now. He gained confidence. He flourished. He was focused on being the best he could be. He was technically and musically perfecting his craft.”

Charles found the Interlochen experience very gratifying. “I had been homeschooled for three years prior. I felt like I lacked the sense of community that can only be found in that school environment,” he says. “It gave me a warm feeling to be accepted and part of something so exciting.”

High School and Beyond

When Joan Holland, resident instructor of harp at Interlochen, met Charles, she could tell he had great musical ears. In class, for example, when a person’s cell phone went off, he would immediately play the tune on the harp. “The longer we were together, I found out his ears are a cut above,” she says.

Charles also had a “deep understanding of traditional classical music,” she adds, noting there is a peacefulness about him when he plays. “He’s a very strong player. He never played to show off or prove what he could do. It always came from the center of the music.”

At the end of his senior year, he received the very prestigious Young Artist Award. “Every teacher was on board for Charles,” Holland says. “I love this kid. When he plays jazz, you really hear his inner voice as well as his jazz intelligence. It’s great. It’s extreme.”

After graduating from Interlochen, Charles applied to and was accepted by seven schools: Berklee College of Music, The Juilliard School, Oberlin Conservatory of Music, University of Toronto, The Glenn Gould School of Music in Toronto, the University of Illinois, and the University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre, and Dance.

His mom encouraged him to choose Berklee in Boston, but there were differences in the harp curriculums affecting his decision about which prestigious school to attend, and Charles waffled between Berklee and Juilliard.

Ultimately, Charles said he would go to Berklee and study jazz if Jessica Zhou, principal harpist for the Boston Symphony, would be willing to teach him classical harp. Zhou agreed.

“When they contacted me to teach him, I was hesitant because I had a full-time job that was demanding, and I was teaching at other schools,” Zhou says, adding, “Charles was a very serious student. He did everything I asked him to do. Through the years, he became more competent in his playing. He had very high standards for himself, but he was always so humble. That is so rare nowadays. I loved teaching him.”

The first time she heard him play impromptu jazz, she was amazed. “He’s so good,” she says. “When he plays classical, he’s such a serious musician. The way he switches it over and plays jazz improv on the harp, you have to be clear-minded to do that. He’s in his element.”

At Berklee, harp professor Felice Pomeranz, who runs The Harp Program at the school, encouraged Charles to apply to the Berklee Global Jazz Institute, a specialized, elite group at the school. He was the first harp student to be admitted to the Institute. “He went kicking and screaming into that audition. He didn’t think he was ready,” she recalls. “But he did things others who auditioned couldn’t do. He impressed some of the biggest stars in jazz who come here and do residencies.”

Pomeranz admits she’s never pushed a student as hard as she pushed Charles. “He has stepped up,” she says. “He’s shining like a star, proving how versatile the harp can be. He’s truly in demand.”

Jazzing It Up

Charles loves the creative element in jazz. “I always feel like I have a little bit more to offer,” he says. “It’s all spontaneous composition, making music with other musicians on the spot. It’s a special feeling.”

He still plays classical music and substitutes with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. He’s also played with the Boston Pops as well as the New York Philharmonic.

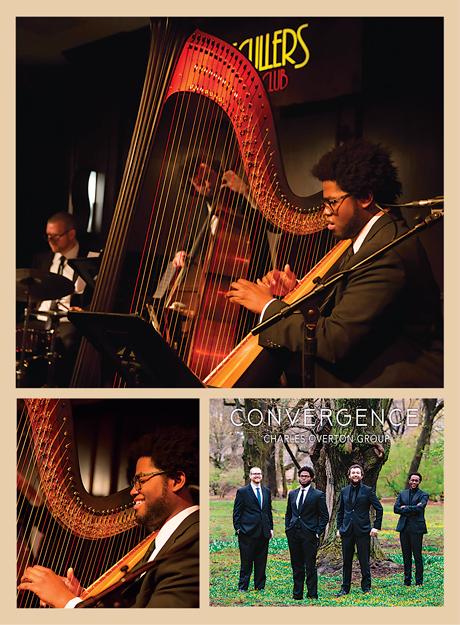

He started the Charles Overton Group in 2016. Members include drummer Peter Barnick, bassist Max Ridley, and saxophonist Greg Groover, Jr. “We play all around, primarily in local jazz clubs in Boston,” says Charles, who lives in Boston. “We have residency at The Outpost in Cambridge, and we played in Washington, D.C., at the Camac Harp Festival.”

Last month, the group traveled to Europe to play at Harps au Max Festival in Ancenis, France. Charles’ mother and father flew to France to show their support and hear him perform.

While studying with masters, traveling, performing, and captivating audiences over the years, Charles has never considered his young life extraordinary. “It was normal to me,” he says, noting he tries to slip home to visit three to four times a year. “That’s all due to my parents. They made it feel like what we were doing together was normal. They never questioned me. They supported me throughout my life in trying to pursue a career in music.”

Photos: American Youth Harp Ensemble, Jonas Tarm