By October of 2017, body image issues, dieting, and anxiety collided with the trauma of a sexual assault to create a perfect storm for Emma Manis. That’s when Emma, at age twenty-two, was diagnosed with anorexia, body dysmorphia (an obsessive focus on perceived flaws in appearance), depression, and anxiety.

The seeds of Emma’s challenges with body image and acceptance were planted when she was an adolescent. Growing up in Chesterfield County, she played competitive soccer, training for hours each day on school and club teams, and later, on an Olympic development team. “When you have a bunch of girls competing together constantly, there’s a lot of rivalry there,” Emma says. “I always had a more athletic build, and I always felt self-conscious about it.” Along the way, Emma experimented with dieting as she fought to feel good about herself.

In any environment, and especially competitive ones, kids can be cruel to one another. Emma’s parents, Lesli and Terry, say they wish they could go back to that period and help young Emma cope with the negative comments their daughter heard from the athletes around her, some of whom were rivals on the field. “If we could have done something different, we would have given her more tools to cope with bullying,” says Terry. “We would have helped her understand that not everyone’s going to like you and you’re not going to be perfect, but that doesn’t lessen your value.”

After graduating from high school, Emma left home to play soccer at VMI on a scholarship, but the military school wasn’t a good fit for her. She developed anxiety and was grieving the deaths of her grandparents, who had lived with her family since she was in elementary school. “I had recently lost my grandparents, and I had gone from losing them to transitioning into a college that was very intense and had a lot of rules,” says Emma.

In the spring of 2014, Emma transferred to Virginia Commonwealth University to study fashion merchandising. She felt more at home at VCU in a creative field and graduated in 2017. But the transition from college to a career and the trauma of a sexual assault that occurred later that year were too much. The new factors, combined with the anxiety and body image issues from her past, led to disordered behaviors around eating.

Once Emma began restricting her diet in response to stress, things spiraled out of control. “As soon as I started losing weight, people commented on how I looked and asked what I was doing,” says Emma. “It put more pressure on me to lose weight.” As a full-fledged eating disorder took root, Emma used a mixture of restricting, binging, and purging to lose a substantial amount of weight in a relatively short period of time.

When the eating disorder was unfolding, it took some time for Lesli and Terry to become aware of how bad things had gotten. Emma no longer lived with her parents, and like many people who battle an eating disorder, she tried to hide the extent of her illness.

Lesli, who is a nurse, had some inkling there was an issue, but the realization set in when the two were on a shopping trip together in Carytown. “When she tried on a dress, I saw her hip bones sticking out, and I had to rest my hand on a table because it felt like my knees were going to buckle,” says Lesli. It was at this point that she remembers telling Emma, If you don’t get help, you will die.

Once Lesli and Terry realized the severity of Emma’s illness, they helped her put a treatment team in place consisting of her physician, a therapist, and a dietitian. As is the case for many people battling eating disorders, Emma’s providers did not accept her insurance, and all costs have been out of pocket. Emma’s parents helped pay for treatment, and they worked hard to ensure Emma took control of her recovery. “I knew her personality,” says Lesli, “and I knew it would backfire if I didn’t take a step back and let her take charge.” Lesli and Terry remained sources of support, but they encouraged their young adult daughter to own the process.

Recovery has been complicated, as Emma expected it would be, but some aspects have been more challenging than others. “I definitely thought the weight restoration piece was going to be the hardest part,” says Emma. “Now I realize all the emotional and mental work that came after the weight restoration was so much harder because once you restore the weight, everyone perceives you as if you’re back to normal.” She found it difficult to meet people’s expectations that she was completely healthy when she still needed to do more work in recovery on her emotional and mental health.

Emma says once she restored the weight and was nourishing her body well, she began to see the disease in retrospect much more clearly. “I was able to reflect and see the damage I was doing to my body and also how depressed and unhappy I felt, even though I was even lower than the weight I had wanted to be in the first place,” she says.

Throughout recovery, Emma’s parents have been supportive. “My parents have gone to discussions both online and offline and really tried to understand it as much as they possibly can,” says Emma. “I don’t think they’ll ever fully understand it because they haven’t been through it themselves, but they’ve done a really good job of investing themselves in my recovery.”

Part of that investment has involved developing a better understanding of the dialogue around disordered eating. “Emma has helped teach me appropriate things to say,” says Lesli, who has learned that the comments many of us make about food and our bodies can be triggering to people like her daughter. Triggers can include comments about a person’s appearance (“You look so good!” or “Does my butt look big in these jeans?”), as well as comments about food (“I shouldn’t have eaten so much” or “I feel bad for eating that piece of cake.”)

Emma’s parents have also discovered the importance of letting their daughter lead the conversation when appropriate. “We’ve learned to ask questions that aren’t too invasive,” says Terry, “and we’ve learned how to give both space and love at the same time.”

During the initial period of recovery, Emma met with her therapist twice a week, her dietitian once a week, and her doctor every other week to have her blood taken for tests and vitals checked. “I quit my job working in menswear because it was such an emotionally draining time,” says Emma. “I needed to make sure I was alive.” Now, several years later, Emma sees her therapist every other week, her dietitian once a month, and her physician every four months.

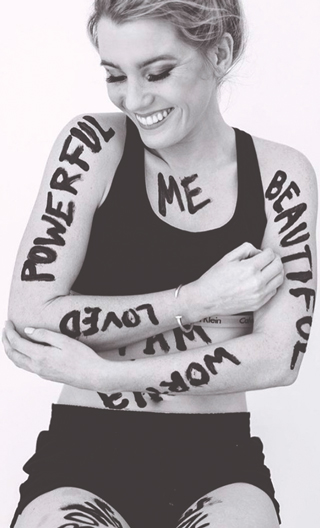

After Emma stopped working her full-time job to focus on recovery, she started pursuing her passions. And she hasn’t slowed down. Around the time of her diagnosis, Emma teamed up with a high school friend, Colleen Hegarty, to develop an online clothing company named EVOLVE (shopevolve.co). Although Colleen left EVOLVE in early 2019, their mission prevails: to transform the way women think about themselves and their clothing through body-positive apparel.

The shop’s name has multiple meanings: First, Emma strives to evolve with women throughout their lives. The shop offers sizes from extra small to twenty-four and focuses on including brands and choices for all different shapes, races, ages, body sizes, gender identities, and abilities. “We want shopping for clothing to be an empowering experience where you get to decide how to make your mark on the world that day in whatever you decide to put on,” says Emma.

Second, Emma hopes to foster an evolution in the fashion industry toward empowering all women through greater inclusion and representation with the ancillary mission to educate members of the fashion industry regarding body image and eating disorders.

EVOLVE gives back to the community through “Shop for a Cause” pop-up events. They partner with other organizations, like college sororities, and donate a percentage of sales to that organization’s philanthropic cause.

Emma is also forming the Beauty Has No Limits foundation, which will raise money to help people with eating disorders fund their treatment because so few insurance companies cover it. “Our goal this year is to give out five $5,000 scholarships,” says Emma. “It’s not a ton of money, but it offsets the cost a little bit.” Emma has also dedicated time and resources to the National Eating Disorder Association Walk to raise money for eating disorder awareness and research.

Terry and Lesli are excited to see Emma use her challenges to help others. “We’re all put in positions to make a difference,” says Lesli. “It’s amazing to watch Emma as she grows stronger and impacts more people.”

Just as Emma worked hard to excel in soccer when she was younger, she has devoted countless hours and resources to her recovery, and with that, her drive to help others. “Recovery and the eating disorder have had a lot of positive effects,” says Emma. “An eating disorder is not a good thing, of course, but a lot of what you learn from your disorder and your treatment is really positive, and you can take these lessons and use them in a really empowering way to help you through the rest of your life.”

How to Help When A Child Shows Signs of an Eating Disorder

The statistics surrounding eating disorders are staggering.

Among mental health disorders, eating disorders have the second highest fatality rate, behind opiate addiction. It is estimated that around 30 million people in the United States will experience an eating disorder like anorexia, bulimia, or binge eating disorder. Although eating disorders are typically associated with females, one in three people with eating disorders are male.

Many eating disorders start out with a fairly innocent desire to be healthy. “Society puts tremendous pressure on people – especially women – to look a certain way,” says Elisha Contner Wilkins, executive director of Veritas Collaborative’s Child, Adolescent, and Adult Center in Richmond, part of a national healthcare system for the treatment of eating disorders. “An eating disorder can start when getting in shape for a specific event like spring break, prom, or a wedding,” Wilkins says.

The majority of eating disorders begin during adolescence or young adulthood; the average age range is fifteen to twenty-five. It is not always possible to prevent an eating disorder, but Wilkins says there are things parents can do to promote healthier attitudes about food, weight, and body image in their families:

1. Create rituals around mealtimes. Try to make this time together as a family peaceful. Save loaded conversations for another time and space.

2. Embrace the idea that all foods fit into a balanced diet.

3. Stop commenting on people’s appearances – even your own. In other words, refrain from criticizing the things you dislike about your own body or praising others for losing weight.

If your child starts to focus on eating more healthfully and exercising more, it’s important to look out for signs that an eating disorder might be taking root. According to Wilkins, some of these signs include eliminating desserts or cutting portions, making excuses for not eating with others, using the bathroom right after meals, exhibiting a change in mood, and engaging in frequent conversation about the desire to look a certain way or become more popular. “It’s also important to look for behaviors like this that might be happening in secret,” says Wilkins.

When these behaviors emerge, Wilkins suggests approaching your child with compassion. “Point out what you observe, not what someone told you,” says Wilkins. “You can say something like, ‘I notice you’ve been cutting back on what you used to enjoy. I’m bringing this to you because I love and care about you, and I want to help.’”

If you continue to be concerned about your child’s obsession with looking a certain way or cutting certain foods out of her diet, you can reach out to a therapist, particularly one who specializes in treating patients with eating disorders. Therapists can provide parents with support and help them develop an effective plan of action.

Consulting the child’s pediatrician can also be an effective next step, says Wilkins. The pediatrician can review growth charts and determine what is happening medically. If a diagnosis is appropriate, the physician can put into place a comprehensive medical exam.

Once a diagnosis is made, parents can look at treatment, which might include working with a team of therapists, dietitians, and physicians. Wilkins encourages parents to be proactive in seeking help. “Undergoing treatment as close to the time of onset as possible leads to less likelihood of a relapse,” she says.

Research has consistently shown that treatment is most effective when provided as soon as possible. Early intervention typically requires less intensive – and therefore, less costly – treatment. Early intervention can also lessen the chances of relapse after recovery. In addition, early intervention can help mitigate the potentially devastating health conditions caused by eating disorders, including heart complications, low red and white blood cell counts, and low bone density.

While Emma Manis has worked with a team of independent providers to manage recovery, some families turn to a treatment center like Veritas Collaborative. These types of treatment centers typically offer different levels of care consistent with the American Psychiatric Guidelines for eating disorder treatment, including both inpatient and outpatient treatment options.

When a child is in outpatient rather than inpatient treatment, families need to be involved in day-to-day care; ideally medical and mental health professionals will provide coaching for family members to help them support their children with refeeding and weight restoration.

Wilkins acknowledges that caring for a child with an eating disorder can be draining on many levels. “Parents need support and a self-care plan to sustain the emotional and mental energy required to do the work of helping their child without burning out,” says Wilkins.

Eating disorder treatment can be arduous and potentially very expensive. Some insurance companies do not cover treatment at all, and the families whose insurance companies do cover treatment may still face high out-of-pocket costs. For information about navigating insurance issues, consult the National Eating Disorder Association at NationalEatingDisorder.org.

Emma Manis is grateful to her parents for helping make her recovery possible, and in recognition of their support, she is forming the nonprofit organization Beauty Has No Limits to raise money for others who need eating disorder treatment but cannot afford it.

Stay Strong Virginia, founded by Beth Ayn Stansfield who helped her daughter recover from an eating disorder, provides valuable support groups and resources to area families impacted by eating disorders. Visit StayStrongVirginia.org for helpful information and insight.

Read more about Stay Strong Virginia in RFM.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Writer Catherine Brown has launched a podcast on eating disorder recovery. Co-hosting with a licensed social worker, they break down stigmas surrounding eating disorders, provide a platform for connection, and help people navigate their own recovery. The pod will feature experts interviews as well as interviews with people who have battled eating disorders.