At age seven, Madeline Frazier of Chesterfield was an active, sociable kid who made good grades and excelled in gymnastics. Her mother, Laura Frazier, describes her as “very independent – the kid you drop off anywhere and you’re like, ‘See ya later.’” But suddenly, everything changed. Madeline became scared of the most mundane daily activities – eating, riding in the car, and going to school.

“Overnight, she went from being a competitive gymnast to where she couldn’t eat or go to gymnastics, and I’m thinking, ‘This is not my daughter,’” Frazier says. Out of nowhere, the once-healthy and self-assured 7-year-old had severe separation anxiety as well as emetophobia, or a fear of vomiting – a phobia which led to food restriction. For the already tiny gymnast, that meant slipping below fifty pounds.

At first, Frazier, who is a nurse, and Madeline’s pediatrician, wrote off the weight loss and behaviors as nothing too unusual. Frazier recalls that the pediatrician determined the symptoms were the result of anxiety, and suggested an antacid. When the nausea and pain worsened, the Fraziers were referred to a gastroenterologist who diagnosed Madeline with gastroparesis, a condition that causes the stomach to empty too slowly, and prescribed an antibiotic.

What Frazier and the doctors treating Madeline did not realize – and wouldn’t figure out until nearly four years later – was that Madeline was actually suffering from PANDAS, a cute-sounding acronym for an anything-but-cute disorder: pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections.

First identified in 1998 by investigators at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), including pediatrician Susan Swedo, MD, PANDAS is an autoimmune disorder in which a strep infection triggers an immune response causing inflammation in the child’s brain. This inflammation leads to a host of troubling symptoms.

The symptoms most commonly associated with PANDAS include rapid-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), anxiety, tics (repetitive, involuntary movements or vocalizations), sudden personality changes, a decline in math and handwriting abilities, sensory sensitivities, and restrictive eating. According to the PANDAS Network, an outreach partnership program of the National Institutes of Health, as many as one in 200 children may be affected, but the disorder requires a clinical diagnosis – a subjective judgment based on symptoms and the patient’s medical history. Though blood tests can confirm elevated strep levels in PANDAS patients, there is no single blood test or brain scan that can conclusively confirm the condition and, as Frazier experienced, getting an accurate diagnosis can be difficult.

The condition is still unknown to many medical professionals, and met with skepticism by others who are unconvinced of the link between strep, autoimmune response, and neurological and behavioral symptoms. Many of those who do acknowledge the link do not know how to treat the illness effectively. Typical treatment protocols involve antibiotics, but doctors may be uncertain about which antibiotics to try, at what dosage, or for how long. A typical 10-day course, for example, such as the prescription a child with an ear infection or a case of strep might receive, is likely not enough to eradicate PANDAS. The PANDAS Network and PANDAS Physicians Network recommend that most children diagnosed with PANDAS receive antibiotics for one to two years, as a prophylactic measure, until the system has had time to kick the strep and heal itself from the ordeal. Corticosteroids can also be helpful in reducing the severity of symptoms. More severe cases may require intravenous immunoglobin therapy (IVIG) or plasma exchange, which can be extremely expensive and is often not covered by insurance. Even with a clinical diagnosis of PANDAS, finding a doctor willing to go all-in on these treatments can be a challenge.

As a result, parents might not get a diagnosis or a treatment protocol from their pediatrician, and might instead learn about the disorder and treatment options in online parenting forums or from friends. Likewise, parents may have to go online to find a recommendation for PANDAS-literate doctors, as they are known, within the small and tightly moderated social media world of PANDAS families.

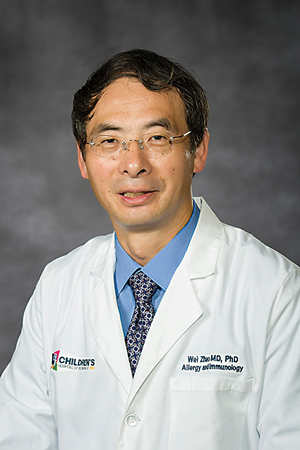

The Richmond area is home to one such doctor, Wei Zhao, MD, chief of allergy and immunology at the Children’s Hospital of Richmond at VCU, and the doctor who was finally able to help Madeline. He acknowledges that an allergist might, at first, seem like an unlikely specialist to treat what presents like a psychiatric disorder. “When the body reacts to something outside the body, we call it allergy, but the strep bacteria has the ability to mimic the body’s structure. The body is trying to react to build immunity,” says Dr. Zhao.

He accepted his first PANDAS patient three years ago, and has since taken on a role as the Central Virginia region’s PANDAS go-to doctor. With few options available to families locally, Dr. Zhao has identified what he calls a critical need in the community.

He has taken on this role out of a desire to help patients – and their families – but he also acknowledges the complexity of the diagnosis and treatment. “I’m not even trying to claim myself as a PANDAS specialist, because treatment takes a multidisciplinary approach, and that requires physicians in different areas to work together.”

It also requires knowledgeable pediatricians, family practice doctors, school nurses, and other professionals to help parents make the connection between the tantrums, phobias, intrusive thoughts, and other symptoms and that case of strep throat or scarlet fever the child picked up weeks, months, or even years before.

Dr. Swedo, who was at the forefront of PANDAS treatment and recovery with NIMH and now serves as the health organization’s chief of pediatrics and developmental neuroscience, estimates that up to 25 percent of cases of kids with OCD or tic disorders (like Tourette’s syndrome, characterized by involuntary movements and vocal expression) may point to PANDAS as the underlying cause.

Dr. Zhao acknowledges the difficulty of diagnosis. “Not everyone will present with the textbook presentation. That’s why, in the medical field, a lot of those patients in the past would be picked up as just ordinary OCD or psychiatric disorders.” But now, due in large part to social media and outreach groups like the PANDAS Network and the PANDAS Physicians Network, Dr. Zhao says that information is more accessible to doctors and parents alike.

One such awareness group is based in Richmond. The Pediatric Research and Advocacy Initiative (PRAI) was founded by local mom Jessica Gavin after her son Dexter was diagnosed with PANDAS at age four. He was labeled as autistic, but Gavin knew that diagnosis was not accurate. “When he was healthy, he didn’t have autism,” she explains. “I went from doctor to doctor to doctor,” Gavin recalls, traveling to Florida and paying expenses out-of-pocket before Dexter was finally diagnosed with PANDAS.

But even with a diagnosis, Gavin still felt lost. “I was sitting in front of my TV crying because my son had this thing called PANDAS, and on came a story about a mom whose kid had a rare disease, and because of her raising money for it, there was a new experimental treatment plan.” Determined to do something to help her son and other kids like him, she reached out on social media. She remembers seeing results quickly, with other moms saying, Yeah, let’s do something about this! It wasn’t easy though, and Gavin is blunt about the challenges. “Running an organization with everybody who has these kids who are dealing with all these issues can be hard because they’re so busy with the kids,” Gavin says.

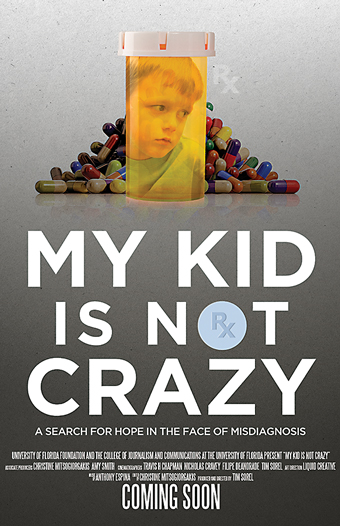

Together with other local PANDAS parents, Gavin started launching committees and working to focus the new organization’s mission. PRAI provides support for families, but it is also committed to raising money for research, education, and awareness. One event that had a major impact in this community, Gavin notes, was a screening of the 2017 independent film, My Kid Is Not Crazy (directed by Tim Sorel), at the Grace Street Theater last spring. The organization invited local doctors to the showing, which was followed by a Q&A with a panel of experts, including Dr. Zhao and Dr. Swedo. “Once the doctors came to the film, it laid the groundwork to build relationships with local practices,” Gavin says, noting that if primary-care doctors can recognize PANDAS, then referrals to specialists can follow.

In addition to raising awareness, PRAI is working to raise funds for further research because so much about the disorder remains a mystery. Even the name PANDAS is up for debate. Similar symptoms have been observed in children with no history of strep. Dr. Zhao notes that other infections, like Lyme disease or Epstein-Barr virus, can trigger a similar autoimmune response that is labeled PANS (pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome). The broader category these disorders fit under is post-infectious autoimmune encephalopathy. Gavin suspects that “PANS and PANDAS are going to actually be the first of many disorders that are linked to the immune system,” and she adds that “some of what we’ve known about psychiatric illnesses in the past is based on wrong thinking. We’re going to have to change the textbooks.”

One of the biggest challenges for doctors and parents is that PANDAS presents differently from individual to individual. In cases where the underlying infection was never diagnosed to begin with, its role as the root cause of other symptoms can go overlooked. That was Frazier’s experience with Madeline. Looking back, Frazier speculates that her daughter’s initial infection was likely strep in the gut, which caused Madeline’s stomachaches and was then followed by a rapid change in personality.

The antibiotics prescribed to Madeline for the gastroparesis worked to treat her undiagnosed PANDAS. Because the disorder is an immune response to the strep infection, often clearing up the infection will also clear up the troublesome symptoms of PANDAS, and that’s what happened with Madeline. With that early success, Frazier had no idea that the illness, though it responded to treatment, had been misdiagnosed. On antibiotics for a year, “Madeline got better. Slowly, but surely she got better.”

Unfortunately, it didn’t last.

Madeline was nine years old when she stopped taking the antibiotics, and she regressed severely. Frazier says, “It’s like a rug was pulled out from under her, and she just fell, and everything got ten times worse.” Terrified of being alone, Madeline followed her mother everywhere, even to the bathroom, and she couldn’t face going on a school field trip. At a loss for ways to help the struggling fourth grader, the pediatrician advised Frazier that perhaps Madeline needed inpatient psychiatric care.

Like the parents featured in the film My Kid Is Not Crazy, Frazier knew inpatient care was not the answer. That answer came, finally, in a “lightbulb a-ha moment.” Frazier had heard of PANDAS the way many parents do at first, by word-of-mouth. Initially, she didn’t think it could apply to Madeline because she had not been diagnosed with strep. But then she thought about the initial stomach pain and how Madeline had responded to that first round of antibiotics. “Then I was piecing it all together.” She recalls the night she had the epiphany. Unable to sleep, she lay awake thinking, How soon can I call the doctor?

Dr. Zhao was able to help Madeline with a high dose of strong antibiotics. At age twelve, she is now living a normal life, making straight As, writing a fantasy-adventure novel, and spending lots of time in the gym working on gymnastics skills. However, Frazier understands that PANDAS symptoms can recur. “Once in a while, we still have little flares where she gets wiped out and can’t really function, but you’re almost afraid to say it because you don’t want them to get sick again.” Though the disorder is in remission, and Madeline is happy and healthy, her mother admits, “I’m haunted. I worry every day.”

Frazier says she has talked to many parents who think their children might fit the criteria for a PANDAS diagnosis. Her advice to them? “Act fast. You’re playing with brain inflammation – don’t wait.” Gavin, too, advises parents to be proactive when approaching the pediatrician. She encourages parents to go online – to the PANDAS Physician’s Network – and locate the published research themselves. “Download papers and bring them to your pediatrician and ask, ‘Why are we not doing this?’ Arm yourself with information and bring that to your pediatrician.”

Dr. Zhao agrees that initial diagnosis should happen in the pediatrician’s office, and he says that one goal of the practice at VCU is “to have more close engagement with primary doctors, to talk to them, and educate them so they can educate us, based on their experience.” He hopes that soon, pediatricians will feel more comfortable taking on the mild cases, caught early, and doing basic tests and treatments. Then, he says, “for more complicated patients’ cases, we would be there [at Children’s Hospital of Richmond at VCU] for families.”

For Madeline and her family, Dr. Zhao helped restore some normalcy to her childhood, but had her mother not questioned the initial diagnosis, there could have been a different outcome. Gavin, too, knows first-hand the important role parents play in advocating for their children, making doctors listen to their concerns, and compelling them to act.

“Parents are a pain. We’re going crazy ourselves because it’s like our kids’ brains are on fire,” says Gavin. It’s her mission with PRAI to continue to direct families to useful resources, and to raise money for research to better understand what is going on inside the heads of kids like Dexter and Madeline.

As for Madeline, she does not remember much about her illness, though she recalls thinking that she “would never be better… never get to have fun and be a kid.” Today she has dreams of being a famous author and maybe a psychologist, too. Her advice to kids who are suffering from PANDAS is

to “believe that some day everything will be okay again, because it will.”

Parent-Powered Research Is Off and Running!

Parent-Powered Research Is Off and Running!

When Jessica Gavin of Midlothian looked out at the crowd of parents and caregivers gathered at Grace Street Theater to watch a documentary in March, she knew she was on the right track.

Gavin, the founder of the PANS Research and Advocacy Initiative (PRAI), is committed to raising money to help improve diagnosis and treatment options for PANDAS/PANS. The screening of the film, My Kid Is Not Crazy, was the first large-scale fundraiser for PRAI, which has raised more than $75,000 since its launch eighteen months ago. The film’s director, Tim Sorel, Susan Swedo, MD, of the National Institutes of Health, and Wei Zhao, MD, from the Children’s Hospital of Richmond at VCU, took questions at the sold-out event.

“PRAI is raising the money so we can fund our first research project for PANS. We have Jonathan Kipnis from UVA as our scientific advisor as well as Dr. Zhao and Dr. Sanford from VCU,” Gavin said. “We are working on creating a think tank to help guide how we approach funding research.”

Gavin has sold awareness bands, flowers for Mother’s Day, hosted the documentary, and held a fundraiser at Blue Mountain Brewery. “We also raised some initial start-up costs online through Crowdrise.”

Gavin‘s first 5K is slated for September in Richmond. She will also hold community walks for the cause in North and South Carolina. Although Gavin is a rookie in the world of nonprofit fundraising, her energy is unwavering.

“Every dollar makes a difference. It plays an incredibly important role in getting our kids the care they need.” says Gavin. “Our goal is $100,000 by October 1, and all proceeds will go toward research into PANS.”

To learn more about PANDAS/PANS visit pansadvocacy.org.

Photos: Rexford Studios