At the start of the new year when people consider changing their eating habits, they are probably thinking about subtracting elements – like carbs, sugar, and processed foods – instead of adding protein sources. But there is some interesting science to show that incorporating insects into your diet could have numerous positive outcomes.

Wait! Stay with me! I know the thought of eating insects, spiders, millipedes, scorpions, and their kin sounds unthinkable to most Richmonders, but many people around the world consume all of those. In fact, almost 2 billion people worldwide – including Central and South America, Africa, Asia, Australia, and New Zealand – eat bugs on a regular basis. That is more than 25 percent of the world’s population. It is only Western societies that seem to have a negative perception of giving insects a space on the plate.

And, to be clear, people across the globe do not eat insects simply because they can’t afford pork or beef. Eating insects is often seen as

a treat or delicacy. It is simply a learned behavior.

Bug Eating History

Insects were on Earth millions of years before humans, so it doesn’t seem that far-fetched that somewhere along the way, someone tried eating them. Bug eating is called entomophagy, a word derived from the Greek words entomon (insect) and phagein (to devour).

Eating insects isn’t a new thing: Edible insects and their larvae were depicted on cave paintings found in Spain dating from 30,000 to 9,000 BC. A little closer to home, the first people of North America were avid bug eaters. In fact, ears of corn infested with corn earworms were sold for more money than corn without the caterpillars.

The Skinny on Eating Insects

Today, nearly 2,000 insect species have been identified as edible, each with distinctive qualities, textures, and flavors. Insects are versatile – they can be baked, fried, pureed, ground into flour, and turned into salts. They can be added to savory dishes, baked into sweets, or even stirred into a cocktail. Beetles (and their larvae, such as mealworms and buffalo worms) top the list as most popular, followed by caterpillars, bees/wasps, ants, crickets, and grasshoppers.

But just because we can eat bugs, should we? The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations thinks so, and for the last decade, has championed insects as the most viable alternative source of protein to meat because of their ecological friendliness.

Many insect species are rich in protein and good fats, as well as high in calcium, iron, and zinc. Farm-raised crickets, for example, can contain double the amount of protein in chicken, more calcium than milk, and more iron than spinach.

It’s Good for the Earth’s Health, Too

Insects also have environmental advantages. They emit considerably less greenhouse gases than most livestock (especially cattle), they don’t generate large quantities of waste that can pollute rivers and lakes, and they require a tiny fraction of the fresh water pigs and cows need to survive. Currently, the rearing of livestock is responsible for 18 percent of greenhouse gas emissions, a higher share than the transportation sector, and agriculture consumes about 70 percent of freshwater worldwide. Mealworms, on the other hand, can grow to maturity with only the moisture they get from their food.

In addition, crickets require less than 4 pounds of food to produce just over 2 pounds of meat. That’s twelve times less feed than cattle, four times less than sheep, and half as much as chickens. And insects have less waste: 80 percent of the body is considered edible compared to 40 percent for beef. Because of all this, insects tend to have a better “feed to food” conversion efficiency ratio than livestock. And there’s more agricultural science to support this: Approximately one-third of the world’s cereal production is fed to animals. Think about the huge impact it would have if most of that was used for feeding people instead.

Looking at Logistics

Unless you own a farm, you’re probably not raising livestock. Unlike with many meat protein sources, raising insects for personal consumption requires a relatively small space and minimal work. Plus, insects grow rapidly and reproduce quickly, thus providing a supply that regenerates often.

If you are not up to starting your own bug farm, then consider what insect ingredients might already be crawling through your backyard. If you ate the weevils and tomato hornworms that show up in your summer garden, there would be little need for pesticides to protect your veggies. Think about the health improvements in the environment and humankind if we could eliminate the use of chemical garden powders and sprays.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting eating raw bugs. Applying high heat, such as by baking or boiling, is the only way to ensure there are no parasites on the insects. I’m simply pointing out these backyard bugs as a way to get you thinking about the ecosystem where you live and how humans could change the way they fit into the food web.

While it might seem like there are more than enough insects pestering you while you’re trying to spend time in your yard, more research is needed before Americans, Canadians, and Europeans join the rest of the world and start regularly cooking with insects. Before industrializing insects as food, checks and balances need to be established to ensure native species are not over-harvested, thus upsetting a natural balance that has taken millions of years to achieve.

Also, eating insects is not for everyone. I’m not just talking about the ick factor. Eating bugs could trigger allergic reactions in some people. Anyone with an allergy to crab, lobster, or shrimp should steer clear of foods containing insects.

While I might not have persuaded many people to enjoy an insect-filled meal today, hopefully I’ve done what we always try to do at the Science Museum of Virginia: Blow your mind and make you question your world.

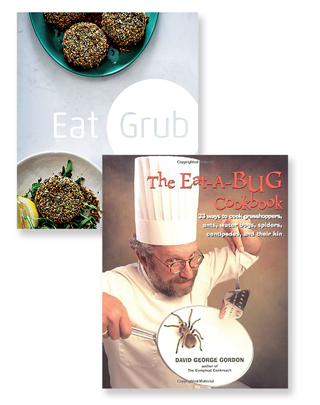

If you’re inspired to try an insect recipe, we’ve used two sources at the Museum to get ideas: Eat Grub by Shami Radia and Neil Whippey and The Eat-a-Bug Cookbook by David George Gordon. Gordon said it best when he wrote these encouraging words to his readers: “Bug appétit!”