Find out how talking about suicide and listening to people who want to share their experiences can save lives in this article by expert Anne Moss Rogers.

Let’s face it, when it comes to communicating with your kids, you’d probably rather talk about sex than suicide. But as a mom who lost a son to suicide in 2015, it’s a conversation you need to have with a young person – even if everything looks okay on the outside.

My son Charles was the funniest, most popular kid in school and the last person you’d ever expect to take his life. When I looked back later after learning more, I saw obvious signs of suicide and recognized times I should have listened more and lectured less.

At this point in my grief journey, (read about Anne Moss Rogers and her advocacy work in RFM here) I have forgiven myself for the 5 percent of parenting I did imperfectly, choosing instead to focus on the 95 percent I did right – and remembering the beautiful life that went with that.

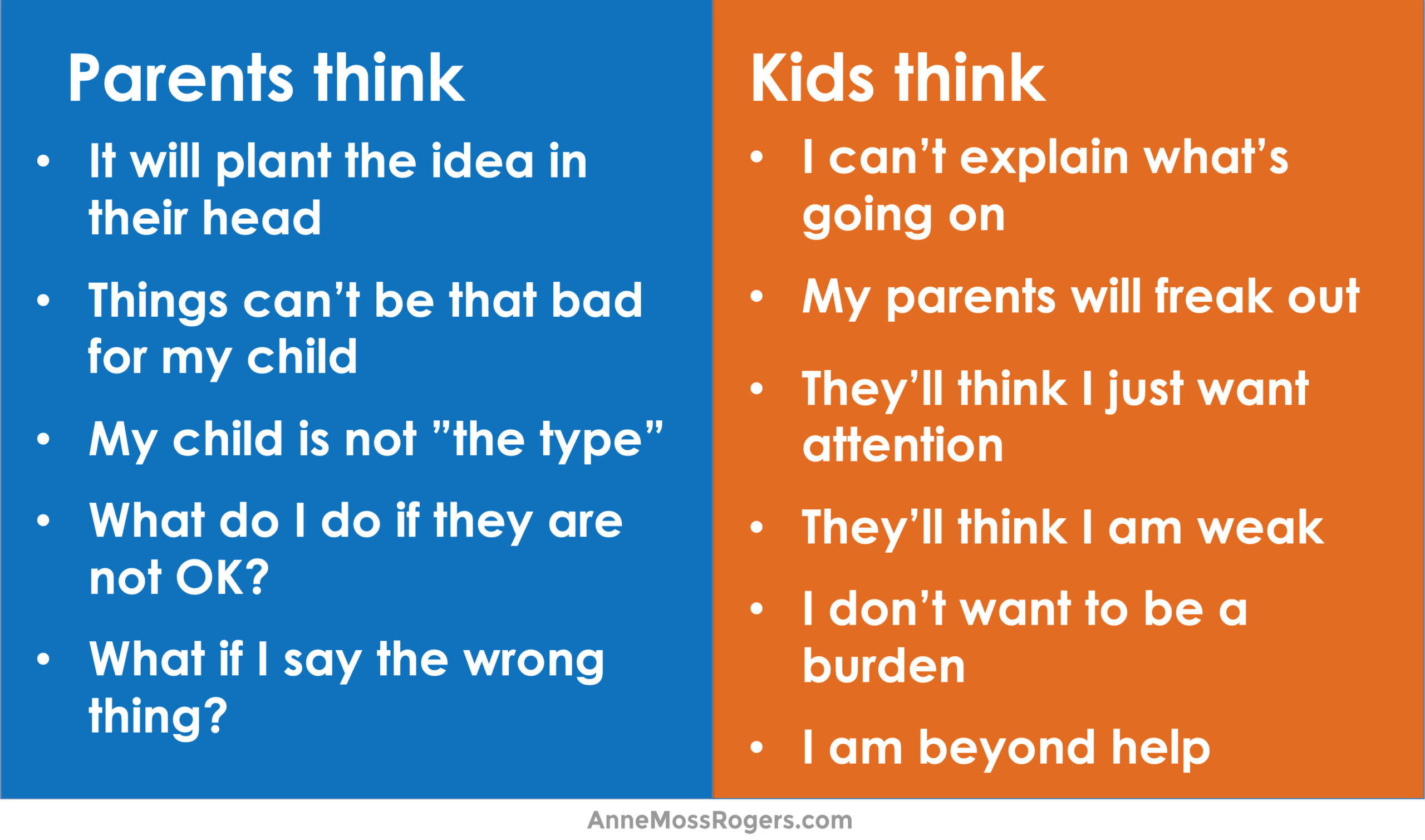

This article will focus on how to get past the roadblocks of very uncomfortable, but necessary, conversations that include suicide. Because it saves lives. We will explore two questions: Why don’t people ask? Why don’t people tell?

Why don’t we ask, “Are you thinking about suicide?”

We don’t want to ask it, we don’t know to ask it, and we don’t think it’s okay to ask it. But if you want to know if someone is thinking about suicide (often called suicidal ideation), you need to ask directly. That starts with a conversation and includes a lot of listening.

Many believe asking the question plants the thought in someone’s mind. That’s a myth. And studies have shown that talking about suicide gives a person the chance to talk openly about something they may have wanted to talk about for days, months, years, and even decades.

The biggest reason we don’t ask is because we fear the answer. What if the person says yes, and this huge problem you can’t solve is left in your lap? The good news is that it’s not your job to fix it. You can only support and help that person save their own life. If a young person says they have been thinking about suicide, don’t freak out. Take a deep breath and recognize that right now, they are alive and talking to you, which means some part of them wants to live. Next say something like, “I’m really honored you trust me. I am here to help in any way I can, but in a minute I’m going to shut up and listen. How long have you felt this way?”

Then, do just that: more listening and no lecturing. And no fixing at first. Allow the person to feel heard. It really is the greatest gift you can offer someone.

Don’t undervalue showing up and being there for someone in their despair. I’ve had people tell me they didn’t kill themselves because someone said, “You look distressed – do you want to talk?” One man said a hug saved his life.

And if they say no, they haven’t been thinking about suicide? Do listen and take the opportunity to establish yourself as a trusted adult that young people can come to when they need to talk.

Often people think that their loved ones aren’t the type or wouldn’t really take their own life because of family, friends, a pet, or their personal success. It’s hard for us to imagine life would be so bad for a young person with so much untapped potential that they would resort to killing themselves.

We inadvertently dismiss their pain as something they’ll get over or outgrow. Unless we have lived experience with suicidal thoughts,

we don’t understand how it can come in like a lightning bolt, take a brain hostage, and push that person toward thinking suicide is the only option to stop the brain pain.

It’s an uncomfortable topic and question. Putting the question in context helps ease discomfort. For example, you can ask, “Sometimes, after a big breakup, a person doesn’t want to live anymore. So, I need to ask – are you thinking of suicide?”

Why don’t people struggling with suicide tell someone?

They think they might lose their job, a relationship, or your respect. They fear being rejected, ridiculed, looked down upon, or seen as weak. That’s just for starters, and these are all valid concerns.

People who are thinking about suicide need others to meet them where they are. We often say things like, “You have so much to live for,” when we need to say, “I had no idea. I’m so sorry. I’m listening. Tell me more.” They don’t need us to coax them out of despair or push them into the light. Just listen.

Believe me, these conversations will always feel uncomfortable, and your brain will try to rationalize you out of it. Work through the discomfort. I don’t want you to feel regret or worse, lose a child, niece, nephew, cousin, or best friend’s child because you thought you weren’t qualified to ask the question, “Are you thinking about suicide?” If you can listen with empathy, you are qualified.

If you suspect someone might be thinking about suicide:

1. Engage them in private conversation.

2. Listen with empathy – no fixing.

3. Ask directly: “Are you thinking about suicide?”

4. Connect the person with help or support (another friend or relative or the crisis hotline: 9-8-8). You can also call the crisis line for guidance while you are with that person.