A few years ago, a video Snap was made public where white students from an area middle school held down African American students in sexually explicit positions while making racist remarks.

Naturally, parents were appalled. Social media responses like “This is not who we are” and “I can’t believe this is happening in 2017” were prevalent. But the truth is that as a nation, this is who we are. This stuff happens, and it will continue to happen until all of us take responsibility.

Trying to figure out how something like this could happen in our own community, people were quick to assign blame. One comment read, “The kids are not the problem, their parents are the problem!” And another said, “The kids learn this stuff at home!”

Sure, kids learn a lot from what they hear and observe. But we are missing the point: Children also learn from what they are not hearing.

Most white parents don’t talk to their kids about race.

Why? First of all, most of our white parents didn’t talk to us about race.

Second, unless you are part of a racial minority, the topic of race just doesn’t come up naturally.

My daughter has two dads. Naturally, we’ve had picture books with two-dad families since before she was born. One of her friends in preschool is being raised by a single mom. This woman was intentional in connecting with us because she wanted her daughter to see different kinds of families. But if your child grows up in a mom/dad household, she won’t naturally learn about non-traditional families until she meets one.

In his book, White Like Me, Tim Wise explains how many white children encounter race for the first time. For context, remember that most white parents were not taught about race by their own parents. As a result, talking about race still feels very uncomfortable. To avoid saying anything wrong, they often choose not to say anything at all.

And then the child sees a person of color at the store… and makes a comment – loudly.

You know what most of us do when our kids make embarrassing comments in public. We tell them to be quiet or to lower their voices. Our embarrassment takes over. Maybe we were taught that “it’s not nice to say those things,” so we feel that a stern look will teach our child the same.

When children talk about race, people of all colors and shapes (at least in the United States) clam up. Why? Because we have a code that says what’s appropriate and what’s not. And when kids speak up, without understanding this unspoken code, parents are scared. What is your kid going to say? What will that then say about you as parent? And that’s when it happens – the parent says, “Shhhhhh, that’s not nice.” And the child learns that it’s not okay to talk about race. Or see race. Or that there’s something inherently bad about race.

My daughter did it, too.

My daughter and I had dinner at a hot dog place the other day. As we walked out, she stopped and smirked at someone. I turned and noticed a young black man with a big afro. The man looked back at her and smiled. She pointed at his hair and looked at me.

This could have been one of those moments. These situations always catch us off guard, so I took a breath and tried to slow myself down. He had no idea why this little white girl was singling him out. I went down to her eye level and said, “Hey, honey, pointing at other people makes them uncomfortable. What are you trying to show me?” She responded, “He forgot to pull his comb out of his hair!”

That was not what I expected her to say. I hadn’t even noticed the pick in his hair. I took a breath, trying to explain, “Oh, it’s a hairstyle. You see, black hair is able to hold it, so if you pay attention, you’ll see that people do it all the time.”

I wasn’t sure if the young man heard our conversation, so I told her, “I worry he might be embarrassed because we are staring.” I suggested she tell him that she was intrigued by his comb. A social butterfly, she went and told him, “I love the comb in your hair.”

Next time, here’s what you can do.

Instead of running from the embarrassment, slow yourself down and clarify. Then, make sure your child understands that the reason we avoid comments like these is to shield the other person from feeling judged.

When you tell your child “it’s not nice” to comment on something they see, then the focus is on your child, instead of the effect on the other person. And, when you don’t discuss this with him, he may conclude that there is something inherently wrong with what he saw – and that it must not be spoken about.

Your child is not the first to bring up race (or other differences) inappropriately. He is still learning! Most people will appreciate that you educated him, instead of just hushing things away.

Let’s open up the conversation.

Our kids have much to learn. We can’t teach them everything. And it’s impossible to understand the struggle of each minority group.

But we can allow open conversation, even about uncomfortable topics.

When I hear about kids using racial slurs or exhibiting bigoted behaviors on social media, I don’t know what their home life is like. But I’m fairly certain they don’t engage in dinner conversations about race. I wonder if they talk about the generational impact of segregation. Do their white parents talk to them about how it must feel for a person from a minority to be singled out? Do they know that many black kids do talk about race at home? Or, maybe some African American parents don’t talk to their kids about it either, in an attempt to finally move past the issues (it’s been such a long time coming).

Sometimes, we hope that if we don’t talk about it, it won’t be real. Countless parents tell me their child “doesn’t see race.” But kids do. And when we don’t talk to them about it, they learn it somewhere else. Or, they stay in the dark. Then, one day, they post a clip on Instagram or Snapchat and end up on national media.

Let’s talk. In our communities and in our families, let’s get uncomfortable in the right way. Because from what we’re seeing around the country these days, kids definitely see race.

Mark Loewen

Mark Loewen

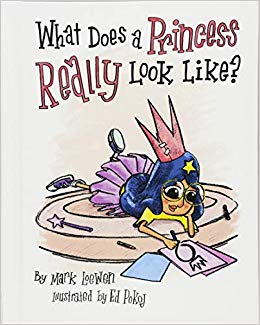

wrote a kids’ book,

What Does a Princess

Really Look Like?

Check it our here.