There was a certain panic in that voice that made me stop and look around. A middle-aged man was standing in front of the theatre; his head darted from person to person as the crowd made its way to the exit. As I came closer, I heard him explaining to a security guard that his 8-year-old had gone to the restroom and not returned to his seat. He continued to yell out the child’s name intermittently while giving more information. “He’s about this tall, brown hair, Redskins’ jacket…” Soon, the movie theater staff was engaged and every few minutes, the man would stop his conversation, and yell out, “Danny, Danny…” with an increased level of anxiety in his voice. By the time I made it to my car, a police squad car had arrived.

We have all been there. One moment your child is by your side and the next, he is gone. That terrible fear overtakes us.

I watched the news that night and looked online because I couldn’t get that man’s voice out of my head. There was nothing. So, my assumption is that, as in most of these situations, there was a reunion and a happy ending.

But what if the worst has happened? What if your child has disappeared? John and Revé Walsh’s 6-year-old son, Adam, was abducted from a Sears store in Florida. He was later found murdered. The Walshes were so dismayed by the lack of organization and attention on the part of the law enforcement community that they focused all of their energy on changing the system. In 1984, they helped pass the Missing Children’s Act of 1982 and the Missing Children’s Act of 1984. These bills led to the establishment of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), which maintains a toll-free hotline number (1-800-THE-LOST) to report a missing child or the sighting of one. John Walsh later hosted the television program America’s Most Wanted which was integral in the capture of numerous criminals.

The Statistics

So, is this something you and I need to worry about? Yes and no.

In 2014, there were 466,949 entries for missing children under the age of eighteen in the FBI’s National Crime Information Center (NCIC). Two-hundred thousand were familial abductions. Fifty-eight thousand were non-familial, but in half of these, the perpetrator was a person the child knew. One hundred and fifteen were stranger abductions. Of these, one hundred resulted in a murdered child. So, while there are a high number of kidnappings, there are also a very high number of recovered children and a very low mortality rate.

Part of the reason for the high success rate is the work of the NCMEC. Since it was founded in 1984, the organization has assisted law enforcement in the recovery of more than 205,550 missing children. Their recovery rate for missing children has grown from 62 percent in 1990 to an amazing 97 percent today. The majority of the children who are reported missing are found within a day of disappearance.

NCMEC also operates CyberTipline to handle reports of suspected child sexual exploitation. As of January 2015, the Cyber Tipline has received more than 3.3 million reports of child sexual exploitation since it was launched in 1998.

Familial Abduction and Children with Special Needs

While the media is inclined to sensationalize stranger abduction and we, as parents, might fear it more, a case marked as “familial” may be just as dangerous. Abby Potash, who now works at the NCMEC headquarters in Alexandria, starting

working there after her son, Sam, was

taken by his father.

Sam had been with his father over a weekend for visitation; he was due to return to camp the next day but never arrived. Abby’s first thought was that they had been in an automobile accident and she was frantic. But when she visited her ex-husband’s apartment she found that all his belongings were gone. Letters sent to his relatives confirmed that he had taken Sam away with the intent that his mother would never see him again.

Abby went to the police and to every missing child service she could find. Her older son, Sean, made a Find Sam website. “NCMEC was a great help,” she says. “They put his picture in an advertising booklet with nationwide coverage.” And one police detective helped a great deal by keeping in close contact with her caseworker at NCMEC. “I found my ex had cleaned out Sam’s college fund and was using all the cash to keep his whereabouts hidden. He also got new identity documents for him and my son, as well as a death certificate saying I was deceased!” When Abby’s ex husband finally ran out of money, about six months later, he sought assistance from a distant cousin in Texas who, coincidentally, had received a mailer about a missing child. That child was Abby’s son, Sam.

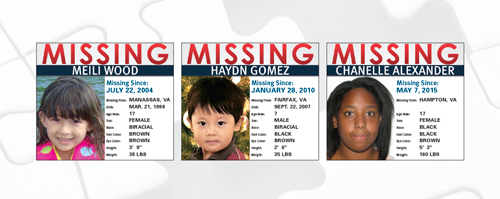

Abby says people might be less concerned with familial abduction because the child appears to be safe. “But they don’t realize that when a child is stolen from a parent, they are stolen from their siblings, their classmates, their pets, their whole life. I now work with parents to help them find their missing children.” Her advice? “Get those pictures out there, contact as many media people as possible.” And she adds, “Usually someone has seen something. It can take a lot of time. Don’t give up.”

If you are the parent of a child with autism, yours is a unique challenge. Experts say half of children with autism have a tendency to wander from their safe environment. Many of these children may also be non-verbal. The NCMEC has a special set of protocols to follow when a child with autism is missing. Children with autism often seek out small or enclosed spaces, or gravitate towards places of interest to them, such as places with animals, trains, roads, heavy equipment, fire trucks, or bright lights. They are especially attracted to water. Parents should keep a list of their child’s special interests and locales that might appeal to them. These places should be checked first when a child with autism is missing.

By talking to those who are close to your child now, you will prepare them in case your child does someday go missing. Tell these people about any particular interests your child has, such as water, roads, trains, trucks, or lights. Tell them about anything that frightens your child – like animals or loud noises. Instruct people who might find your child to stay with him until help arrives, but not try to get too close or initiate the kind of physical contact that might frighten him or cause him to run away.

The AMBER Alert

One important resource available to parents and law enforcement officers is the AMBER Alert system. AMBER stands for America’s Missing Broadcast Emergency Response and was created as a legacy to 9-year-old Amber Hagerman, who was kidnapped while riding her bicycle in Texas and then murdered. The Department of Justice administers the system, teaming up with broadcasters, state police, and state transportation officials. AMBER Alerts interrupt regular programming and are broadcast on radio and television and on highway signs. AMBER Alerts can also be issued on mobile devices, over the Internet, and on lottery tickets. In order for an alert to be issued, officials must have reason to believe abduction occurred and must have some other identifying information about

the perpetrator and/or the victim.

Keeping Your Child Safe

We all know it’s impossible to guarantee our children’s safety at all times. Making more rules for our kids can be cumbersome, but rules give children structure to turn to when they find themselves under pressure from others. According to the NCMEC:

1. Your children should know their home telephone number, their parents’ cell phone numbers, their home address and how to call 9-1-1.

2. Identify a safe neighbor they can go to in the event of an emergency.

3. If at all possible, children should not play alone outside. The buddy system is always safer.

4. When walking or biking, children should also be in pairs.

5. Tell your kids they can’t change their plans or destinations without permission from a parent. Most kidnappings occur when a child is on his way to school or home between the hours of two and seven o’clock. Kids need to know that they can never get into a vehicle without parental permission.

6. Teach your children the tricks predators may use, like needing help to find a lost dog, or offering candy, or toys. Because adults almost never ask children for help, your children need to be comfortable saying no to requests for help from adults who might have ulterior motives. That goes for adults they know as well, since most kidnappers are someone the child knows by sight, like a neighbor or family acquaintance, for example.

7. Tell them to notify you of anyone who crosses a boundary, such as touching them or invading their personal space or asking them to go to a different location or keep a secret.

Sergeant Scott Downs of the Virginia State Police handles missing children cases for Virginia. He says, “One thing that is hard for many children is to say ‘no’ to an adult. Have your children role-play, saying no when an adult is asking them to do something that does not feel right.” Children should trust their instincts and not be embarrassed to react to them.

If you have raised an exceedingly polite child or an introvert, he or she needs to be taught to say no, mean it, and fight back. More than eighty-three percent of children who escaped abduction used kicking, screaming, and pulling away to escape.

One of the best ways to keep your children safe is to ensure that they feel comfortable talking with you about difficult topics from the beginning. Sgt. Downs teaches parents a program on keeping children safe from predators. One component of the program is Take25. Take25 suggests that once a month, you set aside at least twenty-five minutes to talk confidentially with your child about what is happening in his life. This is a scheduled time to feel safe sharing feelings and concerns with you.

This planned time together can open the door to intimate conversations that might otherwise never occur. Sgt. Downs says: “Many parents have said to me that this one change has opened up communication with their kids on so many levels.”

Sgt. Downs advises that when your children begin to reveal things to you that are sensitive, to avoid overreacting. You want to keep the communication lines open. Even though kids may tell you things that are difficult to hear, be careful in how you respond because the most important thing is that they feel they can confide in you without repercussion.

The good news is that as parents and caregivers, we can take actions that can greatly reduce the chances of a child ever being abducted. And if it did happen, organizations like NCMEC and tools like the AMBER Alert System have greatly increased the odds of reuniting a family with a missing child. Interestingly, both of these durable and practical institutions were initiated by parents who lost a child forever. So, never ever underestimate your power as a parent.

What to do if Your Child is Missing

1. Immediately call your local law enforcement agency and provide your child’s name, date of birth, height, weight, and descriptions of any other unique identifiers such as glasses and braces.

2. Tell them when you noticed your child was missing and what clothing he or she was wearing.

3. Request law enforcement authorities immediately enter your child’s name and identifying information into the FBI’s National Crime Information Center Missing Person File.

4. After you have reported your child missing to law enforcement, call the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children at 1-800-THE-LOST (1-800-843-5678). In Virginia, go to the State Police website: vsp.state.va.us

5. If your child is missing from home, search through closets, piles of laundry, in and under beds, inside large appliances, vehicles – including trunks, and anywhere else a child may crawl or hide.

6. If your child is missing in a store, immediately notify the store manager or security office. Then call your local law enforcement agency. Many stores have a Code Adam plan of action in place that would help prevent someone from leaving the premises with your child.

7. To initiate an AMBER Alert, contact Virginia State Police Missing Children’s Clearinghouse at (804) 674 2026.