When artists Catherine Roseberry and Rob Womack married in 1983, they knew they wanted to start a family as well as a business that would allow them to be around their child all day.

When artists Catherine Roseberry and Rob Womack married in 1983, they knew they wanted to start a family as well as a business that would allow them to be around their child all day.

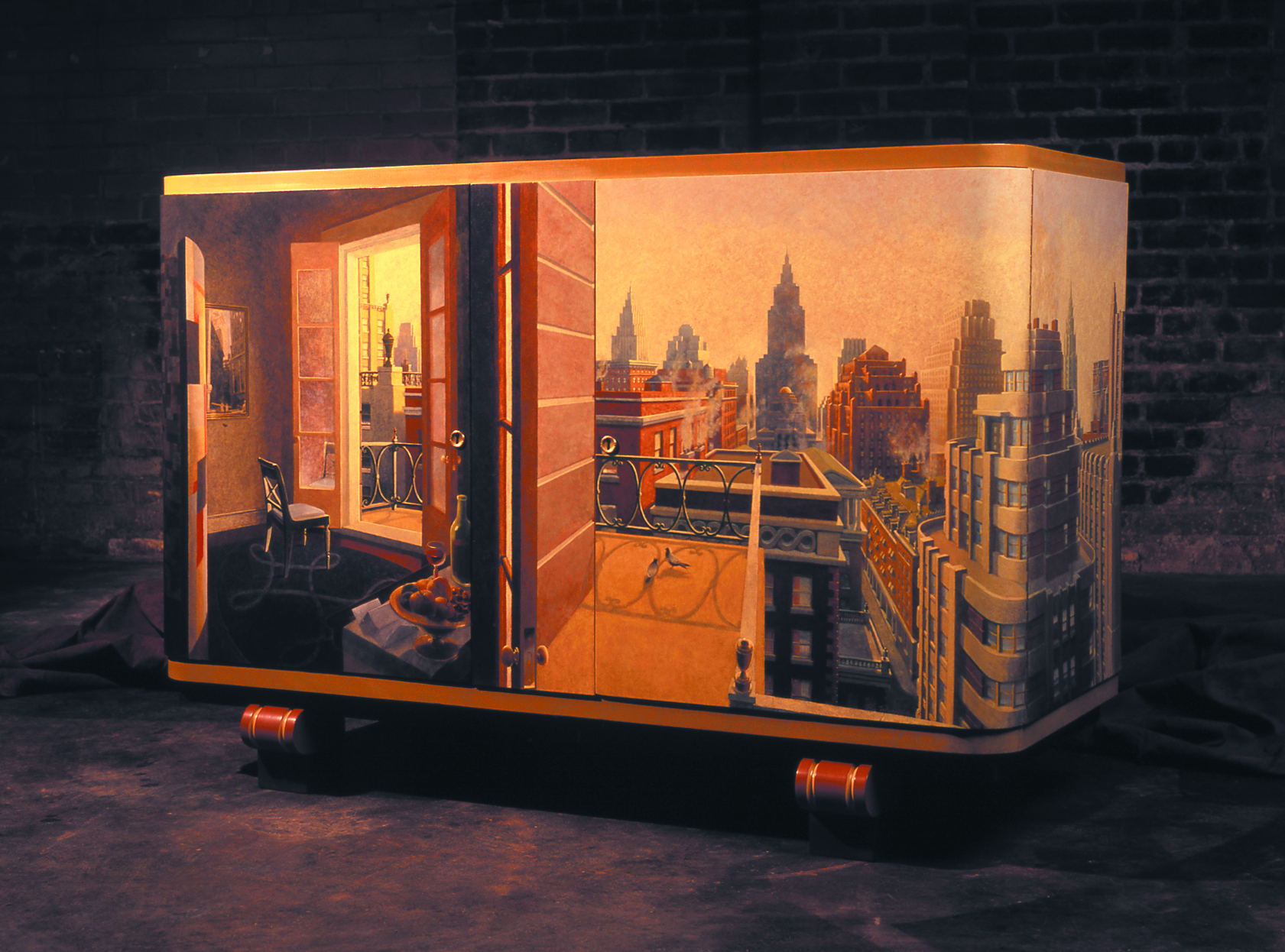

That’s when Coloratura was born. The couple, who met at Virginia Commonwealth University, turns furniture pieces into works of art. About fifty pieces of their work is on display in Coloratura at 35: A Retrospective, an exhibition at the Branch Museum of Architecture and Design that runs through August 19. (branchmuseum.org)

Like any new venture, it took them a while to get the business going and to buy a house large enough for their burgeoning business and a family. “Our house was built in the 1830s and it has a nice big yard,” Roseberry says of their Henrico home. “It was a fun place for a kid to grow up.”

Roseberry was thirteen days shy of turning 40 when the couple’s daughter, Cassie, was born in 1997. They had tried to conceive for three years. That experience of wanting a child and not being able to conceive was the inspiration for one of Roseberry’s pieces in the show called Elusive Joy that documents the yearning to have a family.

Roseberry put her artwork second to her daughter’s needs when Cassie was growing up. She and her husband homeschooled their daughter from fifth grade through high school. “The upside of homeschooling for me is that you get to go through high school twice and you get much smarter,” Roseberry says.

Cassie was a major component of how the couple worked and the pieces they produced. “We had to be creative with our resources,” Catherine says, noting that creativity included scheduling their time.

She admits at times it was difficult for her to find herself after Cassie was born. “It took me many years to stop fighting my identity as a mother,” she says. “I was so entrenched with seeing myself as an artist.”

She admits at times it was difficult for her to find herself after Cassie was born. “It took me many years to stop fighting my identity as a mother,” she says. “I was so entrenched with seeing myself as an artist.”

People began perceiving Womack as the face of the company because he was turning out more art than Roseberry at the time. “It’s just been in the past few years that Cassie has been in college that I could flip back,” she says. “I felt like if you take on the responsibility of having a child, you do it the best way you can. It may mean swallowing your previous identity for a while and it may be hard to see when you can be yourself again.”

Roseberry wanted to set a good example and often worried that Cassie wasn’t seeing her mother’s dedication to her art. “I wanted to do the best I could do,” she says about being a role model.

Raising Cassie was more important to Roseberry than concentrating on her art at the time, but now that Cassie is in college the intensity of parenthood has eased up for Roseberry and she can get back to focusing on her work.

Her experiences as a parent have fueled her recent artwork. Four of her pieces in the show deal explicitly with parenthood, again reflecting the couple’s experiences. Her work now focuses on the condition of women and women’s struggles.

The couple’s creative process begins with the selection of a piece of furniture that they find everywhere from flea markets to auctions. “Sometimes the pieces speak to us,” Womack says. “We work a lot with art deco, mid-century modern and Empire pieces.”

Womack studies each piece of furniture carefully, “learning about its period – the art, music, film, literature, design and cultural influences – to get my ideas,” he says. Roseberry’s work is also inspired by the piece.

The exhibit at The Branch is a study of how these two artists developed “over a 35-year period,” says Branch Museum Executive Director Penny Fletcher. “When you see some of the research they had to do on some of these pieces you are blown away. We think this is a Richmond story. This is their home and we are fortunate to have them here.”