Valerie James Abbott didn’t know how common early hearing loss was until her daughter Bridget was diagnosed at the age of two.

Valerie James Abbott didn’t know how common early hearing loss was until her daughter Bridget was diagnosed at the age of two.

“When she was born, she passed the newborn hearing screening, and we believe she had hearing,” Abbott says. “Somewhere along the way, she lost it. When that was, we don’t know.”

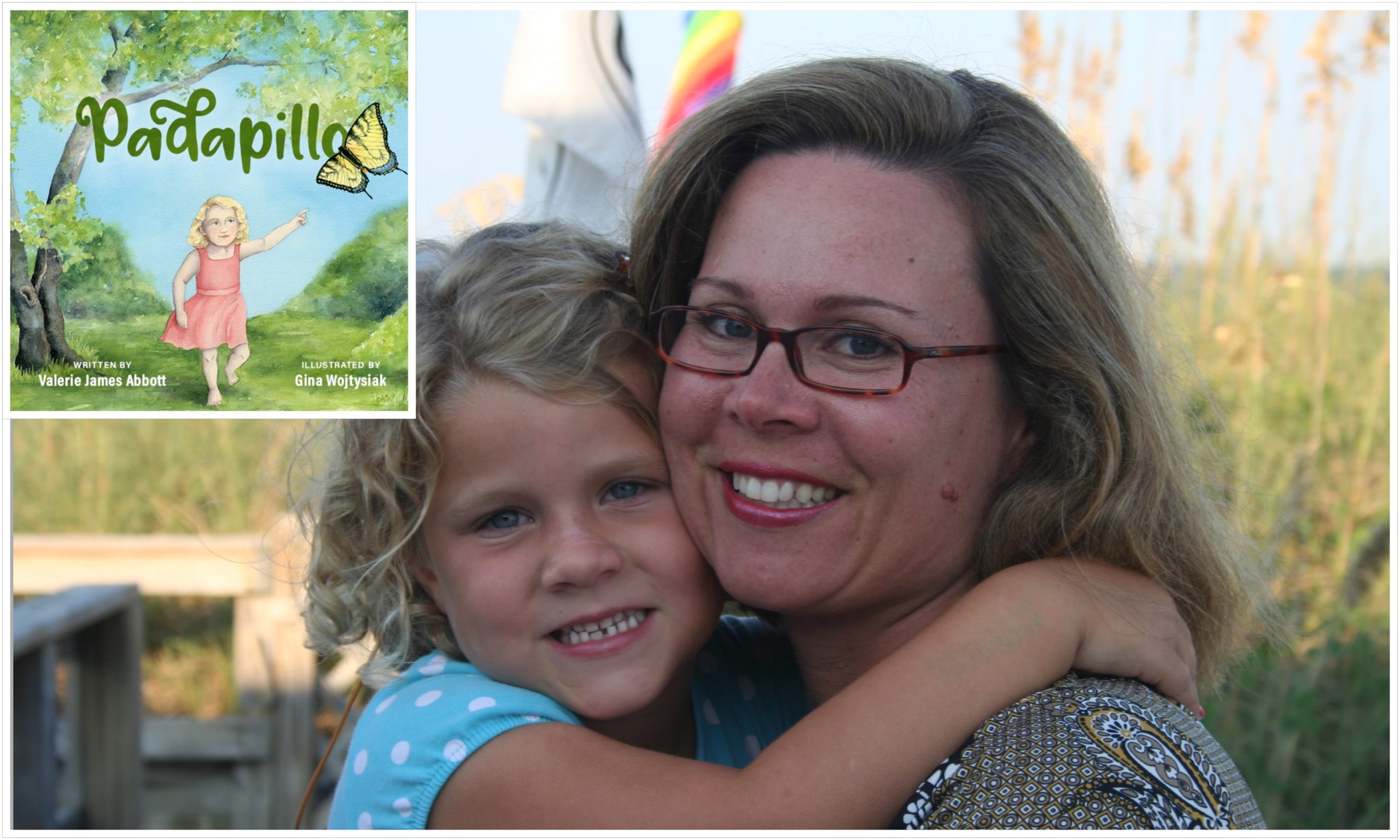

Working through the emotions and adjustments the family experienced after Bridget’s diagnosis laid the groundwork for Abbott’s recent children’s book, Padapillo.

The book is written through the lens of Abbott’s oldest daughter, Mary Clare, who was in kindergarten when her little sister received her first pair of hearing aids. Even though it is fictional, it is based on Abbott’s story of how she and her family discovered and came to terms with Bridget’s situation.

“Every single nugget and situation in here is true,” Abbott says of the book, which was published earlier this year in May.

Surprising Diagnosis

Abbott and her family discovered that Bridget had inherited connexion 26, a genetic mutation. They were unaware of the genetic mutation in their family.

Hearing loss for people with the mutation ranges from very slight to profound and can start at a lower level and progress to a higher degree of hearing loss.

While there is no cure, the condition can be treated with hearing aids and/or cochlear implants.

Abbott credits Bridget’s preschool teacher at the Weinstein JCC for noticing there might be an issue and asking Abbott if she was concerned about Bridget’s speech.

“I said no, but the teacher said, ‘We are,’ ” Abbott says.

The preschool teacher asked Abbott if she would seek out a speech evaluation for Bridget.

“The Infant & Toddler Connection of Henrico came to our house and it quickly became obvious we were looking at a hearing issue. We pulled out some bells from a bag and started ringing them and there was no response,” Abbott says.

Bridget’s diagnosis was shocking for Abbott and her family, especially when Abbott looks back and realizes that the clues were obvious. “She had a speech and language delay and she would make up words,” Abbott says. “We didn’t notice that she wouldn’t hear the doorbell.”

Bridget loved to watch the animated film Tom and Jerry because it’s all visual and “there is no language,” Abbott says.

Once the realization set in, she and her husband conducted a few more tests at home and noticed that Bridget couldn’t hear someone talking from across the room.

The two years following Bridget’s diagnosis were challenging. She needed to catch up developmentally with other children her age. Working closely with an audiologist has helped the family get the services and technology they needed quickly.

Today, Bridget is sixteen and driving. She wears hearing aids and loves them.

“She says it’s part of who I am,” her mom says.

Bridget’s hearing loss has not changed at all since it was first identified and that is encouraging.

“We’ve been hyper vigilant [about testing],” Abbott says. “Statistically, if the hearing loss has not changed for five years, it won’t change again.”

A Book of Hope

Abbott wrote the first version of her book about eighteen months after Bridget’s diagnosis.

“That version was more of me wanting to document what was happening from an emotional standpoint,” she says, adding she named the book Padapillo after one of the words her daughter invented before her hearing loss was identified.

It wasn’t until July 2020 that Abbott was connected to a local publisher.

“I called her and realized the book was possible. We wanted to launch it this May because it was National Better Hearing and Speech Month,” Abbott says. “We were able to do just that.”

Abbott’s message to parents going through the same experience is to know there is “hope,” she says. “Whatever your feelings are, they are valid and it’s ok to be pushy to get the information and support you need.”

Feedback from the book has been positive. Many people are commenting on the fact that it is narrated through the lens of a sibling.

“It’s important to realize that siblings of children with disabilities are part of the experience and are having their own experience,” Abbott says.