Why Smart Kids Worry

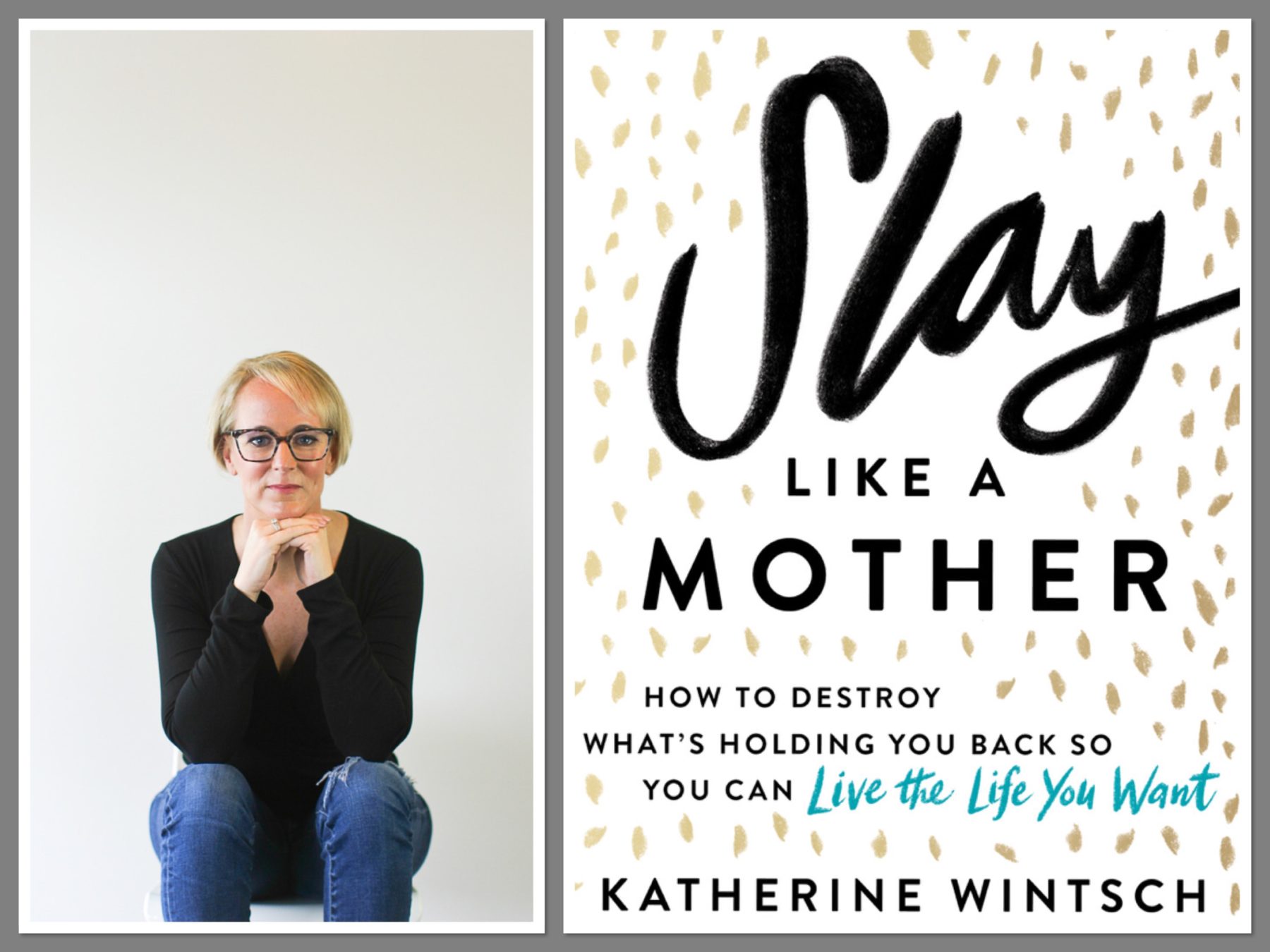

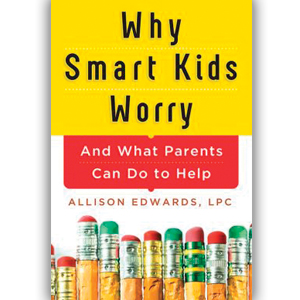

With anxiety being the number one mental health issue among U.S. children (and adults), I wanted a better understanding of why anxiety surfaces and what parents can do about it, so I decided to blog about the new book Why Smart Kids Worry by Allison Edwards. Apparently, gifted children are twice as likely to experience anxiety, as it stems from a discrepancy between their intellectual and emotional development. The fact that we live in an age of worry only compounds the problem. Luckily, while anxious behavior is extremely difficult to change in adults, Edwards claims children can easily learn to work through their anxiety.

With anxiety being the number one mental health issue among U.S. children (and adults), I wanted a better understanding of why anxiety surfaces and what parents can do about it, so I decided to blog about the new book Why Smart Kids Worry by Allison Edwards. Apparently, gifted children are twice as likely to experience anxiety, as it stems from a discrepancy between their intellectual and emotional development. The fact that we live in an age of worry only compounds the problem. Luckily, while anxious behavior is extremely difficult to change in adults, Edwards claims children can easily learn to work through their anxiety.

The first half of Why Smart Kids Worry is devoted to understanding what your child is going through so that you can coach them during difficult times. Edwards believes parents need to stop looking for quick fixes. She argues, “When we try to ‘fix’ kids, we send a message that they aren’t good enough. When we help them accept the part of them that worries and help them channel their anxiety, we empower them.”

One of my favorite parts of this book is how Edwards explains smart. She does a great job giving parents specific examples of the seven different intelligences so that parents can see there’s more to being smart than the couple of traditional intelligences focused on in a school setting. Furthermore, I love how Edwards explains that just because a child may excel in one area, such as Logical-Mathematical Intelligence, that doesn’t mean that they won’t have to work hard to learn something in another area, such as Linguistic. This inconsistency can be frustrating for a smart child, who expects to excel at everything. The best way to handle this is by helping them realize “learning isn’t always easy and that life takes effort.” Rewarding them for trying is one great way to motivate your child. Edwards also suggests empathizing with her when she gets frustrated.

The other issue I think Edwards does a great job of addressing in the first half of her book is that smart kids need appropriate after-school outlets. “Some kids wait all day for school to be over. They don’t enjoy it and live for those few hours in between school and bedtime, where they feel successful. Allowing them this time is a wonderful gift to give to a child,” believes Edwards.

This point really resonated with me because, over the course of my twenty years in education, I’ve been repeatedly confronted with parents who insist on having their child spend their “free time” improving their weaknesses. I remember tutoring this one fifth grade boy in reading three times a week. It was arduous, as he was gifted in Visual-Spatial Intelligence, capable of designing these remarkable rollercoasters on his computer, and he wanted to be drawing, not reading. I encouraged the parents to replace a couple of my visits with art classes, but the mother insisted, since he couldn’t read as well as his twin sister. As a result, the boy’s confidence continued to plummet, feeling like he couldn’t do anything right or at least nothing that his parents valued.

“Anxious kids have lots of mental energy. Their minds are always running, and when they don’t have anything to focus on, they will choose a Default Worry to burn off the excess energy,” argues Edwards. And unfortunately, while the average kid may think Some people die – the smart kid realizes, I may be one of them. Therefore, Edwards devotes chapter three to ‘How Children Process Anxiety and Why It Matters.’ According to Edwards, people can process anxiety by either an inward or outward means. If you are an Inward Processor, who keeps her feelings inside, then it might be hard for you to deal with your child if they are an Outward Processor, someone who deals with their feelings by talking through them. (Or vice versa). Becoming more patient about listening or simply asking fewer questions can help your child process her emotions, claims Edwards, and she offers great examples of both types of processors so parents will know how to separate or invest in their child’s emotions accordingly.

“The ability to take concepts and ideas to the next level is not a choice,” writes Edwards. “[Smart kids] are constantly spinning thoughts over and over, which can help them be brilliant and creative but can also lead to a continual struggle with anxiety.” So if you’re interested in ‘Addressing Your Child’s Anxiety in an Age of Worry,’ tune in later this month for more on Why Smart Kids Worry and put this book on your to read list when it hits bookstore shelves this September.

Follow @WinterhalterV on Twitter for updates on blog posts or like Parenting by the Book on Facebook.

Read my other blog Befriending Forty.